By Vian Faraj:

Part 1

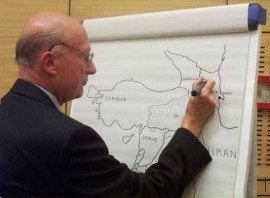

The first division of Kurdistan was made between the Safavid Empire and Ottoman Empire, after the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 and was later formalized in the Zuhab treaty, 1639, according to which Yerevan, the wide area covering the Iranian part of Kurdistan, eastern Georgia, Dagestan, and Azerbaijan was taken by Safavid, while Mesopotamia, including the rest of Kurdistan, western Georgia and west Armenia was for the Ottomans. The story does not end here; the second fractioning of Kurdistan followed the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Soon after the war, super powers settled on the never-ratified Sevres treaty of 1920; consequently, Kurdistan was supposed to get its independence after one year, based on Kurds’ ability to run their own affairs and their desire for independence, according to articles 62 and 64 (1).

However, due to the rejection of Sevres by Ataturk the allies had to renegotiate another treaty known as Lausanne in 1923, according to which Turkey took the biggest and northern part of the newly-divided Kurdistan, Britain took the southern part and joined it to Baghdad, and France attached the smaller Southwest part to Damascus (2). Iran from its side retained its eastern portion of Kurdistan. Hence each segment became a part of the new, man-made and glued states, leaving the biggest non-state nation for so long trapped between four different political systems, four different cultures and four cruel and ruthless régimes.

Throughout these centuries Kurdish people have suffered so many massacres, genocides, and mistreatments; nonetheless none of this has crushed back or stopped them from fighting for their own inborn rights. Men and women were both engaged in working for their own freedoms, yet women’s commitment went way farther because, while men had to fight in order to fearlessly speak out about their realities of being Kurdish, women had to struggle for both their national and their gender rights. Instantaneously territory and gender became both the two indispensible elements of freedom. Thus Kurdish women, despite the reality of their backward, tribal, and narrow culture, still made a very honorable history for themselves; whenever they found a chance they invested it in their favor. So many women, regardless of their clans, religions, and geographical locations, whether they were from south or north, from east or west, found their own way to become prototype women for their society.

Undoubtedly, there are so many women whose stories need to be revealed in this regard, yet in this paper I will first focus on the great female ancestors who paved the road for today’s female Kurdish guerrilla fighters in Rojava to become pioneers world wide. Later on I will concentrate on the impacts that Northern Kurdistan’s political parties and their ideologies, and gender balance activists have made on Rojava’s revolution in both its military and cultural aspects.

Khanzad Sultan

The Soran Emirate was one of the Kurdish Emirates that came into being at the end of the sixteenth century. Its first citing was in Sharafnama (3) stating that the Soran empire was founded by Kelos who had three sons. One of his sons, Isa, was a charismatic leader who managed to gather people around him and formed a self-ruling domain. After the Battle of Chaldiran, the Ottomans succeeded in dominating a large part of Kurdistan; however, unlike other emirates, Soran became very influential, against the wishes of the Ottomans. In 1534, Sulaiman, the Ottoman Emperor, noticed the rapid growth of this little self-governing state. To block it from becoming a force of resistance and a threat to his monarchy, he killed Ezzaddin Shêr, the Soran prince, and gave its authority to Husein Beg of the Yezidi Dasini. (4) Seyfeddin, son of Mir Husein of Soran, with the assistance of prince of Erdelan, regained power from Husein Beg. However, he was betrayed and went back to Istanbul where he was killed by Sultan Sulaiman. (5) After his assassination so many others came to power, including Mir Sulaiman, who ruled Soran at around 1620.

Khanzad, Mir Sulaiman’s sister, was a female warrior commanding, as some stories state, around 30,000 fighters, to protect her Emirate from the Safavids. (6) Actually her authority was over a wide area, nowadays known as the districts of Soran and Harir. Her castle is still on a hilltop only 22 km away from Erbil, the capital of Southern Kurdistan, overlooking the landscape of her territory, authority and power. Evlyia Celeby in his dairy states that:

In the time of Sultan Murad IV [1623-40], the districts of Harir and Soran were ruled by a venerable lady named Khanzade Sultan. She commanded an army consisting of twelve thousand foot soldiers with firearms and ten thousand mounted archers. On the battlefield, her face hidden by a veil and her body covered with a black cloak, she resembled [the legendary Iranian hero] Sam, the son of Nariman, as she rode her Arabian thoroughbred and performed courageous feats of swordsmanship. At the head of a forty to fifty thousand strong army, she several times carried out raids into Iran, plundering Hamadan, Dargazin, Jamjanab and other considerable cities and returning to Soran victorious, loaded with booty. (7)

Khanzad took over the monarchy after her brother, (Mir) Prince Sulaiman was murdered by Lashkry, one of the Soran military commanders. Lashkri could not confront Khanzad due to the fact that she was very powerful and had the heart of a lion. He ran away to Shangal’s mountain with his fellow fighters, but she avenged her brother’s death by sending Lashkry a letter asking him to marry her and to become her partner in ruling Soran. They agreed to meet in Harir, where with her 100 cavaliers she welcomed Lashkri and his men to her citadel. Then, according to the narratives, the next day she with her men killed all of them. Khanzad besides being a woman of honor is also well known for being a lady of state, due to her fairness and constructive policies followed to strengthen her reign. There are so many relics in Harir, Rawanduz and Soran districts proving her ambitious attempts to build a civilized domain, although she only had a brief period of rule, lasting seven years.(8)

References:

[1] Treaty Sevres no:11, treaty of peace with Turkey 1920, see http://treaties.fco.gov.uk/docs/pdf/1920/TS0011.pdf

[2] Treaty Lausanne, no: 16 Treaty of peace of Turkey with other instruments 1923, http://treaties.fco.gov.uk/docs/pdf/1923/TS0016-1.pdf

[3] Establishment date of this emirate is not confirmed precisely: some believe its roots go back to the 13th century, others date it back to 16 century. See Sabah Abdullah Ghalib, The Emergence of Kurdism with Special Reference to the Three Kurdish Emirates within the Ottoman Empire, 1800-1850, University of Exeter, thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies in October 2011, pp. 104

[5] Sabah Abdullah Ghalib, The Emergence of Kurdism with Special Reference to the Three Kurdish Emirates within the Ottoman Empire, 1800-1850 University of Exeter, thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies in October 2011, pp. 104, 105

[6] Soran, or Sorhan, Emirate was one of the longest-ruled Kurdish autonomous area under Ottomans. The emirate gained its full indepedence from the Ottoman Empire shortly after it was taken from Safavid control, in the 1530s, but was later reincorporated into the Ottoman Empire as a semi-autonomous vassal state. Over the next couple of hundred years, the emirate slowly gained full independence for a second time, during the late 1700s and early 1800s, but it was eventually subjugated by Ottoman troops in 1835. See Sabah Abdullah Ghalib, The Emergence of Kurdism with Special Reference to the Three Kurdish Emirates within the Ottoman Empire, 1800-1850 University of Exeter, thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies in October 2011, pp. 104-107.

[7] Evliya Chelebi, a Turkish explorer lived between 1611-1684 in his diary talked about her very precisely. For more information see Martin van Bruinessen, From Adela Khanun to Leyla Zana: Women as Political Leaders in Kurdish History, published in: Shahrzad Mojab (ed.), Women of a Non-State Nation: The Kurds, Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, Inc., 2001, pp. 95-112.

[8] These sources are in Kurdish; Mohammed Tofiq Wahbi, Khanzad and Lashkri, 1960 Baghdad, P, 31 and Asa’d Ado, Did Sorani Khanzad had married? Periodical Karwan, Issue 76, June 1986, pp. 55-60. And Renas Newrozi, The Soran’s Prences Khanzad, Hewrepress, 4/6/2013. http://www.hewrepress.com/wtar.aspx?idw=34

Vian Faraj is a doctorate degree student of Political Science and Administration in Valencia University. She is a writer of three research books, and dozens of articles in Kurdish and English.

.jpg)