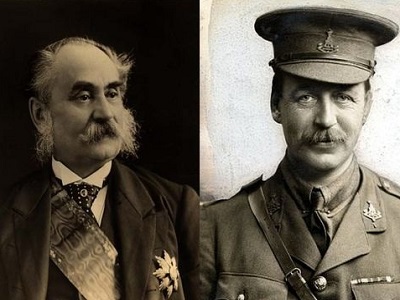

François Georges-Picot (left), and Sir Mark Sykes (right), the men responsible for the secret agreement of 1916 that now bears their names.

By Dr Simon Ross Valentine:

It has been stated with much justification that “the twentieth century was a period of false promises, betrayal, and abuse for Kurds”.(1) Such “abuse” was exemplified in the Sykes-Picot agreement, a secret deal signed by Britain and France 100 years ago, on 16 May 1916.

Sykes-Picot divided the Middle East into British and French spheres of influence, and in so doing denied the Kurds, and other minority groups, the chance of independence. The critics of Sykes-Picot are legion. As one writer recently wrote, this agreement was nothing less than “a colonial ordering device, devised in secret and imposed by force” on the peoples of the Middle East.(2)

Sykes-Picot: A Definition

The historical events leading up to the signing of Sykes-Picot, and the political machinations behind it, are complex to say the least.(3) Even as early as 1915, while the carnage of the First World War still had three more years to run, the allies (Britain and France, with Russian approval) had agreed terms for the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire.

The negotiators behind this agreement were the British diplomat Sir Mark Sykes and the Frenchman, François Georges-Picot. Clandestinely, they discussed the future of the Middle East, dividing up Turkish-held territory, giving what later became Iraq, Palestine and Jordan to Britain, while Syria, Lebanon and parts of northern Iraq were apportioned to France.

Concerning the Kurds, although having been promised autonomy and self-rule, it was decided in 1915 that they would be divided into separate regions in Turkey and Iran. The Sykes-Picot agreement, signed the following year, further divided the Kurds in other parts of the Middle East, namely Iraq and Syria.

Sykes and Picot were experienced diplomats with detailed knowledge and experience of the Middle East. However, despite their undisputed knowledge of the area and its peoples, they merely drew straight lines in the sand to create new borders which failed, amongst other things, to take into account ethnic and geo-political realities.

Britain, attempting to retain its empire after a War that had drained the country financially and militarily, was more interested in stability in the Middle East and the preservation of her oil interests, especially that of the Kirkuk region. As such Westminster, to the chagrin of Kurds dreaming of a country of their own, ignored earlier promises of independence and autonomy.

In January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson of the United States put forward his famous, “Fourteen points”, a blue-print for the post war period. To the delight of the Kurds and other peoples seeking self-rule Wilson’s document “assured” the “non-Turkish races of the former Ottoman Empire” of “undoubted security of life [and] an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development”.(4)

Further encouragement was found in Wilson’s statement: “Peoples and provinces are not to be bartered about from sovereignty to sovereignty as mere chattels and pawns in a game. Every territorial settlement involved in this war must be made in the interest and for the benefit of the populations concerned.”(5)

Such praiseworthy, pious rhetoric however came to nothing. On hearing of the details of the Sykes-Picot agreement, the Americans, and the French, initially protested, especially at Britain’s claim to the Kirkuk region. To the dismay of Kurdish nationalists, such US-Franco protests were swiftly silenced by the British government’s offer of stocks and shares in the future development of Iraq’s oil.

Other Treaties Reinforce Sykes-Picot

At the end of the War the Russians, discovering a copy of the Sykes-Picot agreement, made its terms known to the world. Although there was little or no intention by the western powers to aid the Kurds in obtaining a country of their own, in response to the Russian disclosure the British and the French issued a joint statement affirming that the peoples of the former Ottoman empire would be allowed to establish “indigenous Governments and Administrations”.(6)

Despite this joint statement, the terms of the Sykes-Picot agreement were reinforced by later treaties. The Treaty of Versailles, for example, signed on 21 October 1919, reaffirmed the establishment of French and British zones of influence in the Middle East.

The Kurds, undeterred and determined, submitted another appeal for independence at the San Remo Conference, in April 1920. Surprisingly this appeal found much support, vocal anyway, amongst the allies. In the Treaty of Sevres (between the Allied Powers and Turkey), signed on 10 August 1920, parts of Turkey were promised to the Kurds.

Kurdish hopes for independence were dashed however, with the rapid political changes taking place in Turkey. Kamel Ataturk gained a resounding victory in the Turkish War of Independence. The allies, slowly recovering from the ravages of the First World War, were eager not to anger Turkey, a nation united and apparently strong under its Kemalist ideology of Turkish unity. Consequently, the Treaty of Sevres was renegotiated and, in the Treaty of Lausanne, signed in July 1923, all the promises of Kurdish independence were dropped. As Masoud Barzani stated in March this year, “that document [Treaty of Lausanne] reneged on a promise to carve a Kurdish state out of the remains of the Ottoman Empire and allow this non-Arab ethnic group [the Kurds] to have its own home”.(7)

The despair of the Kurds in the wake of the Treaty of Lausanne is expressed well by Kendal Nezan, the Director of the Kurdish Institute of Paris, who states: “By the end of 1925, the country of the Kurds, known since the XIIth century by the name “Kurdistan”, found itself divided between four states: Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. And for the first time in its long history, it was even to be deprived of its cultural autonomy.(8)

The Sykes-Picot agreement was “regarded then, and today, as a monumental act of European betrayal of Arab [and non-Arab] aspirations …”.(9) It illustrated clearly the realities of realpolitik, the politics of self interest, in which governments adopt practicalities rather than make political decisions on the basis of ethics or justice. In essence, this agreement clearly revealed that in the post World War One era, to the British specifically, and westerners generally, the Kurds were nothing more than loose change in a rich man’s pocket.

The key tenets of the Sykes-Picot agreement, an agreement negotiated in relative haste amidst the turmoil of the First World War, continue to influence the Middle East region to this day. Amongst other things it did much, not only to garner the anti-west feeling prevalent throughout the Arab peoples, but also, due to the Arab’s feeling of exploitation and abuse under western colonialism, acted as a catalyst for both pan-Arabism and Islamic militancy.

But most importantly, Sykes-Picot underscored the issue of “the curse of oil”; the effect of “oil-politics” on the Kurdish people, and the fact that other countries have sought to control the Kurdistan region due to its vast oil reserves. In October 1927 the “Baba Gurgur” (“the father of flames”) oil field north of Kirkuk was discovered. As one writer aptly remarked “its discovery marked the beginning of a tragic period of exploitation for the Kurds”.(10)

“Sykes-Picot was an injustice. The lines need to be re-drawn”

Zrar Sulaiman Sulaiman, a 94 year old peshmerga, with the author

The Need to Redraw the Lines

The era of Sykes-Picot is over. The world today is a completely different place from what it was in 1916. With the 100th anniversary of the drawing up of the Sykes-Picot agreement this would be an opportune time to redraw the map of the Middle East.

In January this year Masoud Barzani “called on global leaders to acknowledge that the Sykes-Picot pact, that led to the boundaries of the modern Middle East, has failed, and urged them to broker a new deal paving the way for a Kurdish state”.(11)

As a British lecturer living in Kurdistan, and researching for a book on Peshmerga, I have the privilege of daily talking to Kurds of all ages and from all walks of life. Their views on Sykes-Picot and independence are well informed and animated.

Commander Bahram Doysky is a Liwa, Major General In the peshmerga. He is in command of 3,200 men, stationed on the front line at Bashiq, near Mosul. In February I spent time with him on the front. In one of several interviews I’ve had with him, speaking through a translator, I asked him about Sykes-Picot and the possibility of independence for the Kurdish people. Sagaciously he told me:

“We Kurds have our own culture, language, national anthem, flag, parliament, president and army. We are a distinct race of people. It is time we had a country too”.

At 94, Zrar Sulaiman Sulaiman’s experience as peshmerga goes back to the short-lived Mahabad Republic of 1946-7 through to the guerrilla warfare by peshmerga against the Iraqi army of Saddam Hussein. Earlier this year I spent three hours talking with him about his life as peshmerga. As with General Barham I asked Zrar about Sykes-Picot. With a deep smile on his wizened, sun tanned face, he replied: “yes Sykes-Picot was an injustice. The lines need to be redrawn. We deserve the help of our western friends to get a country of our own”.

At the end of our interview, firmly taking hold of my hand, Zrar, expressing the view of the majority of Kurds, declared: “I am a Kurd. As a Kurd I am waiting for that bright day, when I can clap my hands and say, we got it!”

References:

(1) D. L. Phillips, The Kurdish Spring: A New Map of the Middle East, Transaction Publishers, 2015, p. 3.

(2) Selim Can Sazak, “Good Riddance to Sykes-Picot,” the National Interest, 12 February 2014, http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/good-riddance-sykes-picot-9868.

(3) For a detailed but concise account of Sykes-Picot see D. McDowall, A Modern History of the Kurds, I. B. Tauris, London, 2007, pp. 115-150.

(4) President Woodrow Wilson’s Address to Congress, 11 February 1918, see http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/fourteenpoints_wilson2.htm

(5) President Woodrow Wilson’s Address to Congress, op.cit.

(6) J. Robertson, Iraq: A History, Oneworld, London, 2015, p. 249.

(7) “Barzani: Sectarian conflict made ISIS inevitable, now is time to redraw boundaries with Kurdish statehood”, Rudaw 14 March 2016.

(8) Kendal Nezan, “A Brief Survey of the History of the Kurds”, nd., http://www.institutkurde.org/en/institute/who_are_the_kurds.php

(9) T. A. J. Abdullah, A Short History of Iraq, Longman/Pearson, London, 2nd edition, 2011, p. 91.

(10) Phillips, The Kurdish Spring, op.cit., p. 21.

(11) “Iraqi Kurdistan president: time has come to redraw Middle East boundaries”, Guardian Newspaper, 22 January 2016.

Dr S R Valentine is a lecturer and freelance writer currently living in Kurdistan, and writing a book on the Peshmerga. He would be pleased to hear from any Kurds with personal anecdotes and information on Peshmerga that he can use in the forthcoming book: archegos@btinternet.com

.jpg)