An Irishman recalls a solidarity visit to North Kurdistan back in the 1990s. First published on Rebel Breeze

By Diarmuid Breatnach:

I was anxious for the Turkish airline plane to take off but it was being held up by Turkish State security agents. Two of them were walking down the airplane aisle from the forward exit, casually casting eyes over the passengers of the plane. Not looking at them would have been suspicious and would have conveyed guilt or fear, so I glanced equally casually at them and then away.

Average height, in suits and sunglasses, dark-haired, one of what might be termed “Mediterranean” appearance in his mid-thirties, the other “Middle-Eastern”, forties perhaps. Secret police for sure – not that their profession was in any way secret. Political police. Almost certainly the same ones who had passed us in town a couple of times as we sat in the cafe killing a few hours before we headed for the airport. Nothing secret about that either – nor even subtle, driving a couple of times up and down the deserted street. They wanted us to know that they knew. Knew what we were. Tightening the cords of fear.

The two came slowly down the airplane aisle towards me. I tried not to tense as they drew near ….. and then they passed on towards the rear. I did not turn to look at them. This might have been a regular kind of security check as far as other passengers were concerned but I knew it wasn’t — they were here for us.

So what now? Drag us off the plane? Drag one or two and leave the rest? What would I do if they arrested one or more of the others but not me? Keep quiet until I got back and raise hell there? Or make a fuss here and get arrested as well? Think about it too much and I’d get really scared. Fear can paralyse. Also might send out the wrong signals. Put it to the back of my mind now …… wait to see what happens, then react. Or not.

I didn’t want to be in any prison, least of all a Turkish one — I’d seen Midnight Express. OK, some people, including the original central character of the story, had protested that the film was not true to life, that it made the Turks out to be monsters. But even those people had not defended Turkish prisons. And if even a tiny percentage of Turks were nasty psychopaths, the police, army and prison service were sure to have more than their share. And I knew what those elements had been doing to the Kurds …. which is why we were there.

Time was slowing down. They were still behind me somewhere but caution was telling me not to turn to look. If we were detained, even for questioning only, they’d go through our luggage. Maybe had done so already. I really wished that thought had not occurred to me.

THE KURDS

The Kurds are a huge ethnic group, population estimates varying between 35 and 45 million, with parts of their people spread through the states of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Syria and Azerbaijan, also with a large diaspora over much of the world, the most numerous in Germany (often those we think of as Turks, for example in kebab shops, are actually Kurds). It is what many might consider the Kurds’ good fortune to be sitting on oil and huge water reserves and a very strategic situation between Europe, Asia and the Middle East. But that had turned out unluckily for them. They’d been overrun by the armies of many conquerors and, as is the way of these things, had participated in a fair few of those armies themselves.

The Kurds are usually classified ethnically as an Iranian people and their language as in the Iranian group but the dominant language in the states in which they find themselves, apart from Iran itself, is mostly Turkish, Arabic or Azeri. Although with long-held nationalist ideas, the Kurds had experienced self-government twice and only for a total of eight years, each time under the protection of the Soviet Union: 1923-1929/’30 (Azerbaijan) and for almost all of 1946 (in northwestern Iran).

But neither the British nor the French, world masters before WW2, wanted an independent Kurdistan. The British had bombed Kurdish villages, probably the first deliberate aerial bombing of civilians, in their repression campaigns in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and Persia (now Iran). The bombing was under the command of Squadron Leader Arnold Harris, developer of the area-bombing tactic, essentially to strike terror into civilian populations and damage their infrastructure. He later put his expertise to use against the German population in WW2, including the horrific bombing of Dresden. By then, of course, the Italian Fascists and German Nazis had learned from Harris’ earlier innovation, the Italians using them against the Ethiopians and the Nazis against Gernika and other towns, later over much of Europe and the Soviet Union.

Neither the post-WW1 treaties among the victors nor the upsurge of anti-British and anti-French nationalism and republicanism across the region had done the Kurds much good. Those carving states out of former empires wanted them as big as possible and would brook no independentism from different ethnic groups on the territory they claimed for their state. Kemal Attaturk, who led a secularising and modernising movement in building the Turkish State, denied that there was any such thing as a Kurdish people – they are just “mountain Turks”, he famously said.

In 1946 the USA, by then the top imperialist power, didn’t want an independent Kurdistan either and nor of course did the Shah of Iran and his supporters so, some time after the Soviets withdrew, the Royal Iranian army invaded and suppressed first the Azerbaijan Republic and then the Kurdish one and executed its leadership.

By 1984 the PPK’s communist-led guerrillas, including female units, were fighting a war of Kurdish national liberation against Turkish troops, who were occupying areas, bombing suspected guerrilla bases, destroying villages and forcibly relocating civilians and carrying out atrocities, including torture, rape and summary executions.

In Syria, the Kurds seemed mostly under the tribal leadership of Barzani and Talibani, their peshmergas or guerrillas sometimes collaborating with the Kurds in the Turkish state and more often not. The Assad regime suppressed Kurdish national aspirations and jailed a number of Kurdish artists, in particular musicians.

During the Iraq-Iran War of 1980-1988, the Hussein regime had bombed Kurds with chemical weapons, including mustard gas, in one incident at Halabja killing up to 5,000 and injuring twice as many, mostly civilian men, women and children. But, strange to know now, at that time the western imperialist powers were supporting Hussein’s invasion of Iraq, because Iran was the ‘big monster’ and Hussein was friendly towards the West. Journalists found it difficult to get their editors interested in the massacre story. And the CIA tried to pin the attack on the Iranians! Only when, years later, Hussein had annoyed the western powers sufficiently by invading Kuwait and they soon afterwards went to all-out war against him, did the story suddenly become generally newsworthy and the then Iraqi military commander Ali Hassan Al-Majid become known as “Chemical Ali”. The chemicals came from west-European companies and US satellite surveillance supplied the targeting references.

Following the defeat of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait by the USA-led coalition forces of the time (35 states overall but with Saudi Arabia and British forces next in number to the USA’s), the CIA called on the Kurds to rise up against the Saddam Hussein regime, leading them to believe that the USA would support them and that Hussein’s overthrow was imminent. They rose but neither the external support nor Iraqi-wide uprising was delivered and they faced heavy military suppression and repression with many atrocities, causing millions of Kurds to flee to the Kurdish areas of Iran and Turkey, hundreds being killed on the way by helicopter strafing attacks or by wandering into minefields. Of the 200 mass graves the Iraqi Human Rights Ministry had registered between 2003-2006, the majority were in the South, including one believed to hold as many as 10,000 victims.

The Kurds of Iran had been repressed under the Shah of Iran but after his overthrow by the Iranian Revolution, they also suffered repression by the fundamentalist clerical regime that took power and executions of Kurdish activists took place. This although during the eight-year Iraq-Iran War, two of the Iraqi Kurdish forces, the Barzani-led KDP and the Talibani-led PUK, had supported the Iranians against the Iraqi regime.

LONDON

The earliest I can remember reading about the Kurds was about Turkish State repression of cultural expression by their Kurdish ethnic citizens, banning of language and song, suppression of history and extending even to arrests of Kurdish women who hung their washing out in the red, white and green sequence — sometimes with yellow in the middle — of Kurdish national colours. Being Irish, I felt something of an identification with them, of course I did. Being a revolutionary socialist in addition, I had no love of the rulers of the repressive Turkish State, nor of the fact of its membership of the USA-dominated military alliance of NATO since 1952.

London, a major European city with a population of over eight millions, larger than the entire population of Ireland (but about the same as the latter’s pre-Great Hunger levels), was temporary or permanent home to a large number and variety of people of non-English ethnic background. Foremost in number was my own, the Irish, largely unacknowledged in multi-racial discourse but the opposite in terms of security, surveillance, harassment and racialisation. I had not heard of the Kurds previously but as one becomes newly aware of the existence of something, it tends to start popping up into one’s consciousness in different places. And so not long after reading of them, I found myself at a Kurdish solidarity meeting in London and leaving my email address with them. Which is how eventually, a couple of years later, I sat in a Turkish airplane in a Kurdistan airport, watching Turkish state political police walking down the aisle towards me.

The Kurdish solidarity people in London set up a committee of activists and I became part of it. The idea came up of building trade union links between Britain and the Kurds, for which it was proposed to send a delegation of British-based trade unionists on a tour of Turkish Kurdistan, whose report could then be used to generate further and increased solidarity work. A boycott of Turkish tourism was one tactic being considered by some of us which, if promoted by the trade union movement in Britain, would have a significant impact on the Turkish economy. Friendly relationships already existed between British trade unions and Turkish ones, which were sometimes repressed by their State but the social-democratic and Moscow-style Communist leaderships on both sides had no sympathy for independence movements which they saw as weakening and splintering the workers’ movement within the Turkish state. There were no specifically Kurdish trade unions but large sections of Turkish unions existed inside the Kurdish region and the solidarity committee had contacts there.

Some of us were asked whether we would like to go, for which we would need to be sponsored by a trade union and raise our own air fares and some money for food — but accommodation and travelling expenses within the region would be taken care of. Most of the money would go towards the flights but our spending money, we were advised, should be in dollars or marks. Lira is the currency of Turkey but it would be hard to get and anyway those other two currencies would be more valued.

I was excited by the idea of going but doubted I could raise the money – living little above subsistence rates as I was. Having been accepted by the University of North London on a BA combined studies course of History and Irish Studies and although in receipt of tuition fees and subsistence support, I was nevertheless having to continue working part-time in order to pay the rent on my flat. It was just my luck that was the year that students in Britain ceased to be eligible for Housing Benefit. Teaching Irish language at Beginners’ level to adults and some weekly youthwork sessions was my only employment then, my last welding job having ended some years earlier – around the same time as the final breakup of my marriage.

The part-time employment and full-time studies course would keep me busy enough but by then I was also on the Ard-Choiste of an active Irish diaspora campaigning organisation, the Irish in Britain Representation Group. In addition, I was also on the Branch Committee of my trade union, NALGO (Clerical Section), as a part-time (which meant no time off work for union activity) Assistant Branch Secretary and also occasionally representing workers in the grant-aided NGO sector. These workers were usually managed by a voluntary committee of people who considered themselves left-wing or at least liberal but often treated their staff atrociously and rarely abided by due process in disciplining them or responding to grievances. Their employees worked in very small organisations (sometimes with only one or two employees) and were isolated, deprived of the solidarity of larger workforces and often played off against one another.

How likely was it that my trade union branch would sponsor me, even nominally? I was unsure. The local NALGO leadership at the time was what I considered collaborationist with the Council’s management, rather than fighting for improvement of conditions and salaries. And I was new to employment by Lewisham Council. And if the branch were to sponsor me, how likely was it that they would put up some funds to get me to Kurdistan?

In the end, the branch did sponsor me to go to investigate and report back, also making a contribution towards my plane fare. Surprisingly, my funding included a personal contribution from a middle-management figure in the Council which, although a union member, surprised me considerably, mostly on a political level. She told me later that despite our differences she admired my courage in undertaking the risk implicit in the delegation. The NALGO Irish Workers’ Group, of which I was also an activist, contributed a sum too from their meagre resources, for which I was very grateful personally and appreciated also as an example of internationalist solidarity.

And so, after a mad rush to sort out and renew my Irish passport, which I had never needed to travel between Britain and Ireland but would for most other destinations, I arrived late and stressed out at Heathrow Airport to meet the others of our delegation bound for Kurdistan.

Just in case anything should happen to me over there, I informed a few of my siblings over in Ireland, insisting my parents not be told until I telephoned that I had returned. There seemed no point in them worrying while I was away. We are not very good at keeping secrets from one another and, of course, someone told my mother, as I found out later.

ISTANBUL

The introductions were brief and hurried before we entered the queue for the Departures gate. Arnold, our English interpreter for Turkish, I had already met several times through the solidarity committee. In addition there was a jocular English photographer called Paddy, a London Afro-Caribbean male trade unionist by the name of Damien from North London and an English woman trade unionist called Rose from another part of England. The initial list had contained another two but they had to drop out for various reasons.

It was late afternoon on a cloudy day around four hours later when we landed at Istanbul airport and in the city we booked into a four-star hotel, apparently arranged by our hosts. Just as New York is seen as the main city in the USA but the capital is actually Washington DC, Istanbul is seen as Turkey’s main city but its capital is actually Ankara. That evening we went out for a little stroll around the older part of the city and to eat and a little later, were brought to a pub apparently frequented by the Turkish Left. After a few pints I sang a couple of Irish songs which seemed well-received but cannot now remember which they were.

The following day we learned that our departure on the next leg of our journey had been delayed and so we had time for a little sight-seeing. After coffee in one of our host’s flats overlooking the Bosporus Strait, where we were told that we were on the European side and on the other was Asia, we split up to see some of the sights. With one other I visited the Sultan Ahmed Mosque (“Blue Mosque”) opened in 1616, functioning as a mosque for Muslim prayer but with parts open to non-believers.

A historic monument in Istanbul is the bronze Serpent Column, created from melted-down Persian weapons, acquired in the plunder of the Persian force’s camp after their defeat at the battle of Platea in 479 BCE, erected at Delphi but transferred to Constantinople (heart of the European side of Istanbul) by Emperor Constantine I “the Great”. Listed on the column were all the Greek city-states that had participated in the battle. Although a part at the top was removed, the Column survived a number of disasters, including the tragic burning and sacking of the city at the hands of the Fourth Crusade (although it was a Christian city) by forces under the Doge of Venice Enrico Dandolo in 1204 AD.

Then we got word to be ready as that night we’d be taking a plane to Batman. Batman, really? Not to Robin? They had heard the jokes before, of course. Batman is a town in the province of the same name, south-east of Anatolia or Asia Minor, i.e in Kurdistan but more to the point, was where our hosts were based – the Petrol Is trade union.

On the journey, looking down from the passenger plane, I could see vast mountain areas seeming like a wrinkled and rucked fabric, in many places covered or streaked in snow. A little over two hours later, we landed at Batman airport.

TURKISH KURDISTAN

Batman was a bit of a shock, to be honest. Not so much the very small airport but the town itself, which seemed to be little more than a long and very wide high street forking at one end. A few shops, cafes or restaurants on one side of the road and some half-constructed buildings and empty sites on the other. A cow walked down the street unattended, stopped by a rubbish bin and began to eat waste cardboard; cows’ stomachs of course can break down cellulose and extract nutrition from it – but still, not what one from our parts of the world expects to see in a town.

On a map of the Kurdish area of the Turkish state, Bitlis would appear to be roughly in the middle; Batman is a little over 100 kilometres from there, heading south-westward.

After spending the night in a very quiet and basic enough Batman hotel but with single rooms each, after breakfast of bread, biscuits and coffee, we got a taxi to the regional Petrol Is headquarters, a large building but which seemed almost empty, where we were asked to wait. After an hour the area where we were, somewhat like an auditorium in size but without many chairs, had begun to fill up. The first thing that struck me was that they were all men – even the administrative staff, it seemed – so that I felt sympathy for Rose. She was wearing a long scarf over her head in recognition of the cultural norms of the area and, although I was not at all sure that I agreed with that, in the end it was her decision.

Eventually the President of the regional branch arrived and we sat down with him and a few of his committee, with some other Petrol Is members standing around us. We were drinking chai, light-coloured tea without milk and with nearby sugar-cubes to add to taste.

The discussions were in Turkish, with Arnold interpreting for us and for the union President. After the introductions, the President welcomed “the British trade unionists” who were coming to enquire about conditions and promised the assistance of the union while we were there. Naturally I couldn’t let that go and asked Arnold to translate the following for me:

“For my own part, as an Irishman in a British trade union, thank you for your hospitality. The British state has occupied my country for hundreds of years and we have struggled – and continue to struggle – for full independence.”

The regional President acknowledged the statement but no doubt understood that I was by inference making a point also about Kurdish members of Turkish trade unions. I was interested in precisely the nature of that relationship and a little later probed deeper, with Arnold of course translating. The President limited himself to stating that the union’s HQ in Turkey supported the regional branches in their struggles for better wages and conditions and for freedom to organise. Of course, even if he were an ardent nationalist, he would have to be very circumspect; there were certain to be State spies in the union.

Petrol Is workers were scattered around the region at oil depots and refineries and often living away from home for long periods. Inclement weather could be an issue as could work accidents. Wages were considered generally good but did not keep up with the rising prices of necessities, not to speak of more luxurious goods – a common experience of the working class around the world.

After about an hour he bade us farewell and we were introduced to our driver for the rest of our stay, Genghis.

Genghis spoke little English but was fluent in both Turkish and his native Kurdish. A good-natured man in his early thirties who lived locally with his wife and children, we were to spend a week in his company as he drove us many hundreds of kilometres. His salary, accommodation and traveling costs, we understood, were being paid by the union.

After Genghis dropped us off back at our hotel, I and some of the others fancied a couple of beers with relaxed conversation but were in for a surprise – the area was under islamic norms. Not only did the hotel have no bar – there were no bars. No alcohol? It is amusing now that some of us seemed more shocked by the prospect of no beer than the fact that we were in an insurgency war zone.

There was, however, a shop where we could buy cans of beer. What kind of islamic no-alcohol policy could that be? We asked no more questions, bought some beers and discreetly brought them back to the hotel, piled into one of the bedrooms and relaxed with a couple of cans for awhile.

Paddy and Damien were quite lively and amusing guys, Arnold and Rose quieter. Of the first two, Paddy was the perhaps the funniest. He seemed to think I looked like Sean Connery (some people years ago thought that) and kept calling me “Big Sean”. He was a freelance professional photographer. Damien was a member, like myself, of a NALGO branch but in North London. Rose was not only on the executive committee of her trade union but also on the joint union area committee.

After a while, we separated, each to his or her own room. Next morning, we were to be up at 7am, meet Genghis and begin our investigative journeys. We’d stop off at a cafe for breakfast on the way.

ARMY ROADBLOCK AND A CANNON-SHELL HOLE IN MY WALL

Driving into a town (I can’t remember which one now) we could see light cannon and heavy machine-gun missile impact marks on the walls of houses.

Suddenly ahead was an Army checkpoint and turning back now they’d seen us would be suicidal. There was nothing to do but to drive up and greet them casually. I was thinking either this is purely coincidence and nothing is likely to happen or it is not and something will definitely happen to us here.

One of the soldiers returned Genghis’ greeting, looked at his passengers and asked to see our ID. I didn’t know whether he was entitled to see more than our driver’s documentation but I was certainly not going to make an issue of it as guns trump legal arguments every time.

The soldier went away with our passports and Genghis’ driving licence, presumably to his officer. An Army truck was blocking our view and we couldn’t see where he was. I looked casually around, saw more bullet-holes. Everywhere.

A little later I saw the soldier coming back towards us and I started doing breathing exercises. He handed over our documents and bade us goodbye. Genghis pulled away slowly – damn right!

From a jeweler in Mediyat I bought a silver ring with a black stone set in it. The shops, a row of what looked like sheds, with bars in front but no shutters we could see, were mostly empty. I am not sure whether it was in that town or another that we booked into a hotel, free of charge again.

Bringing my haversack up to my room on the first floor, I looked out the window on to the street below. When I turned back to the room I got real shock: there was a small diameter cannon shell hole in the wall! It might have been only 20 or 30mm but it seemed huge to my eyes. The shell must have gone in through the window without exploding and then into the wall opposite, again apparently without exploding. Still, anyone in the path of that shell would have been killed.

The bed was below the level of the window ledge and any time I wanted to go to the toilet from my bed, I crawled there on my hands and knees – and back again the same way. And you know what? I never felt stupid doing that, either.

It was raining out so we stayed in and, sitting smoking later that night, the front door open so I could see the street clearly, the owner started talking to me and had me brought free cups of chai. He could speak fair English.

Was the room ok, he asked? I asked him about the shell hole. Did I want to change rooms? No, not at all thanks, I just wanted to know what happened (I was thinking maybe a shell wouldn’t land in the same place twice).

Apparently a few days previously, in another part of town, Kurdish guerrillas had ambushed one of the Turkish armoured cars, destroyed it and got away. The Turkish soldiers, enraged, shot up the town, including his hotel.

“I am a businessman. My hotel is a three-star hotel. But because I am Kurdish, the Army can shoot up my place, I get no compensation and me and my staff could have been killed,” he said.

MASSACRE OF CHILDREN

One day Arnold told us that there had been a terrible incident two days earlier – the Turkish Army had killed people in a village – did we want to go? Of course, we did!

He would make enquiries whether they would want us to visit – after all, we might be bringing more trouble on them.

With their agreement obtained, we set off some hours later. I cannot now remember the name of the village, which was reached by a track off the road. The area was pretty level and the houses were single-storey and rectangular, with white or greyish walls, somewhat similar to the adobe houses one sees in westerns set in the southwest of the USA or Mexico. Entering the village, we passed one of the houses, blackened with huge scorch marks.

Invited into one of the houses, firstly I was surprised at the couple of steps up into the building, secondly by the carpets on the floor inside and thirdly by a TV set in the corner. It was just not what I had expected when viewing the buildings from the outside.

They were all men inside (unless there were women out of sight), apparently village elders and some young men. We sat down on cushions on the carpet to hear the story, translated by Arnold.

Two nights earlier, men had come and knocked at the victim’s house, the one with the scorch marks, saying that they were guerrillas and asking the son, a young man, to come out to talk to them. His mother said “They are not guerrillas” and asked him not to go. He replied that there would be trouble for the family if he did not and so he would go. (What his mother was implying was that the men outside were either soldiers in disguise or State proxy assassination squad people). The son left and they heard him and the others walk away.

After a little, the young man’s father picked up his gun (it is common for people in those areas to have a gun) and went out after his son. A little later, firing was heard down the track.

Eventually, when people went to investigate, they found blood on the ground in some places but no bodies. Their belief was that the son was being mistreated in some way, the father intervened and perhaps shot some of the men but that he and his son were killed too. Then the surviving men took the bodies away.

But worse, much worse was to come, which was what had brought us out there. For the Army arrived and announced a curfew on the village and, that night, a vehicle (the words sounding like a “panzer flamethrower”) had driven up and incinerated the house, the victims including six children. They showed us the photo. It was hard (sometimes still is, thinking about it) not to cry, not to scream in rage.

We said we would tell who we could, thanked them and left. I imagined in turn being the son, then the father, then the neighbours. I did not want to imagine being the victims in the house. We were quiet in the car for a long time.

DIYARBAKIR

Diyarbakir is the capital city of Turkish Kurdistan, a city then of maybe a million or more in population (the estimate for the metropolitan district now is 1.7 million). The Turkish State has had a policy of forcing the Kurds out of their small towns and villages – especially those in the mountains – and directing them in one manner or another to the big city. Such a population reallocation makes the countryside easier to control, removing ‘the sea (the people) that the fish (the guerrillas) swim through’, to paraphrase a famous phrase of Mao-Tse-Tung. The British did it in Kenya and the USA in Vietnam, in somewhat different manner but the principle is the same. Of course revolutions happen in cities too and urbanisation tends towards proletarianisation of the majority, which may cause a different kind of problem for the Turkish ruling class in the long run.

Genghis left us at the hotel and headed home, about 50 kilometres. He wanted to see his wife and children and he’d also heard that the Turkish police had called at his house and questioned his wife. She seemed to be ok but he was worried. And so were we.

Handing in our passports at the hotel registration, we filled in our forms and a boy took them to the local police station as required (this had not been the case in Batman or in Istanbul). We had of course described ourselves as tourists.

While we were eating, the boy returned with the passports and said something to Arnold, who smiled. “He says the police said ‘They are not tourists’,” Arnold told us in response to our queries. My heart gave a little jolt – but what did I expect? Of course they were keeping an eye on us. And letting the boy hear, knowing he would communicate it back to us …. intimidation? Kind of reassuring because what would be the point of intimidation if they were going to arrest us anyway, or worse? Well, maybe to soften us up a little beforehand ….

I pushed the thoughts out of my mind.

The following day we had a number of meetings arranged, the first at a kind of municipal building, was with trade union representatives: teaching, municipal administration both manual and clerical, health workers’ unions. It was slow work since everything had to be translated – ours mostly into Turkish, I think and theirs into English for us. These were much more explicit about their problems with Turkish State repression: censorship, cultural eradication, arrests, threats, a few assassinations by the State proxy so-called Mujahadeen. This was their reality, day in, day out.

About a year later, looking at a list of the names of Kurdish activists assassinated by these State proxy gangs, I recognised the name of at least one of those we had met and talked to, a woman teacher. And felt guilt, the thought that maybe our visit had been part of the decision to kill her. But of course, all Kurdish activists were and are vulnerable, even sometimes abroad – and the Kurds want their stories told out there in the world.

Another meeting took place in what they were calling their human rights centre and here I got the impression of the human rights people working closely with the Kurdish political party – not the PKK, which was banned but perhaps a reformation of it in part, to comply with Turkish laws and allow them to stand in elections. They already had municipal councillors but were heading for Turkey-wide elections. Having the status of a member of the Turkish Parliament in Ankara didn’t really protect one that much, as a number of elected Kurds have found over the years.

For some reason we were kept waiting there for over an hour, although other people were coming and going. I was hungry and not impressed but then, what did I know of what other concerns they might have? Eventually we got to talk to a couple of the human rights people and the politicians. They were very concerned to talk in terms of human rights and not Kurdish independence or even autonomy. With all the people hanging around and listening (which I thought a most inappropriate way to have our meeting), it seemed unwise to push them on that issue. Also, these people too were in constant danger of arrest and even assassination.

We never made any promises to anyone, except that we would report back and try and get publicity for their struggles. We outlined the possible outcomes, such as more media coverage or our trade unions taking up a policy of solidarity with them … but we could not even guarantee that.

Later we wandered through a market area; Damien was anxious to buy a kilim rug and haggled with the seller until they reached agreement. I know that haggling is expected but it is something I cannot do and I left empty-handed.

Back at the hotel, we received a phone call from Genghis – he’d collect us the following day and drive where wished to. His family was ok, the Army had just asked where he was, his wife told them he was away on a driving job for the union but she did not know where.

THE ANCIENT AND OLD

We did get to see some other things, not so directly connected with human rights, conflict or politics.

The Zoroastrian monastery, looking like a fortress standing on its own but I cannot remember where it was. We were received courteously, allowed to see the church and served chai. Did the Army bother them? Rarely but sometimes, was the reply.

Zoroastrianism or Mazdayasna, is the oldest monotheistic religion on record and one of the world’s oldest active religions. Its number of adherents generally world-wide is declining but was reported recently to be increasing somewhat among some of the Kurds. With a single god and good-bad split influences, along with free will and responsibility for one’s actions, it would seem to have influenced the creation of the Judaic faith, which in turn led to the creation of Christianity and, somewhat later, Islam.

The religion’s Wikipedia page contains this possibly contradictory entry: “Recent estimates place the current number of Zoroastrians at around 190,000, with most living in India and in Iran; their number is declining. In 2015, there were reports of up to 100,000 converts in Iraqi Kurdistan. Besides the Zoroastrian diaspora, the older Mithraic faith Yazdanism is still practiced among Kurds.”

Nomads

Another time we drove past a group of nomads, their black tents pitched wide, their flocks of sheep nearby. I would have loved to have talked to them but we were expected elsewhere without time to stop. These were probably Yoruk people.

Ancient site threatened

Hasankeyf is an ancient settlement area along the Tigris river in the south-east of the Turkish state, i.e in Kurdistan. Although it was declared a conservation area by the Turkish Government in 1981, it is now threatened by a dam to be built by the Turkish Government of today. Even back then when we visited, the threat was known although further away.

With a history spanning nine civilizations, it should have World Heritage status. According to Wikipedia:

“ The city of Ilānṣurā mentioned in the Akkadian and Northwest Semitic texts of the Mari Tablets (1800–1750 BC) may possibly be Hasankeyf, although other sites have also been proposed. By the Roman period, the fortified town was known in Latin as Cephe, Cepha or Ciphas, a name that appears to derive from the Syriac word (kefa or kifo), meaning “rock”. As the eastern and western portions of the Roman Empire split around AD 330, Κιφας (Kiphas) became formalized as the Greek name for this Byzantine bishopric.

“Following the Arab conquest of 640, the town became known under the Arabic name حصن كيفا (Hisn Kayf). “Hisn” means “fortress” in Arabic, so the name overall means “rock fortress”.”

The site we visited was of the caves, rather than the city. There were thousands of man-made caves, of which we only saw a few. Paddy displayed his Arabic phrases with an elderly man sitting outside a cafe, while we bought some chai. Up to fairly modern times, people had lived in some of the caves, we were told.

Doomed lovers

In Cizre, over 166 km from our Batman base, we went to see the alleged grave of Mem and Zin, star-crossed lovers without any apparently religious significance but whose grave is cared for and visited by many. We were allowed to enter but there was not much to see – the interesting content is in their story, written down in 1692 and which is performed in a mixture of prose and poetry.

Mem, a young Kurdish boy of one clan and heir to the “City of the West” falls in love with Zin, of the “Botan” clan and daughter of the Governor of Butan. Their meeting is during New Roz, the ancient fire-festival of the Kurds still celebrated today (often with political independence symbolism) but their union is prevented by a man of a different clan who some time later causes the death of Mem. Zin dies mourning at his grave in Cizre, being buried beside her deceased lover.

Bakr, the author of Mem’s death, is killed by the victim’s friend and he is buried near the lovers so that he can witness their being together. However, his hatred is such that it nourishes a thorn tree to grow, sending roots deep into the earth to separate the two lovers, even in death.

Sadly, I knew very little of this wonderful story then and had to look it up on the Internet much later.

Workers on a cotton plantation

On another occasion, on impulse we pulled in off the road at a cotton plantation. The manager politely made time for us, talking about the product, its cultivation etc. Although most Turkish cotton is grown in the Aegean region, there were fields of it here. The cotton grown in Turkey is long-threaded, with fewer joins, therefore higher quality, especially for towels: strong and smooth and not too absorbent.

Were his workers members of a union? He didn’t know, that would be their business. They were well treated; in any case, he did not receive any complaints. Would it be possible to talk to some of the workers? Alas, no, they were in the middle of their shift. But he did not suggest an alternative time when it would be convenient.

AT THE IRAQI AND SYRIAN BORDERS

As our time in Kurdistan drew to a close, Arnold asked whether we’d be interested in seeing the Iraqi and Syrian borders. Of course we would! After Arnold’s brief discussion with Genghis, we set off. It is approximately 300 kilometres from Batman to the Border but we might have been around Mardin by then, which is nearer. Our road wound higher and higher through hills into the mountains and we rarely saw traffic on the road; as we got nearer we’d need to be more cautious. In a quiet mountainy area we stopped beside a stream to stretch our legs and for Genghis to take a short break. Always interested in nature generally and water life in particular, I wandered to the stream and to my amazement saw crabs very like the marine shore crabs of home, both in appearance and size. I soon caught one and had my photo taken holding it up.

A middle-aged and young woman appeared on the road and I greeted them in the few words of Kurdish I knew to which they responded with a muttered reply and turned away. It was probably to do with gendered cultural mores of the area but they might also have seen us as something to do with the Turkish state or even foreign intelligence people operating in the area. I released the crab back into the water, watched it make off sideways, its pincers threatening. We got back in the car and drove off towards the Border.

The US-led Coalition forces in March 1991 had imposed a no-fly zone on the Kurdish region of Iraq from which even Iraqi helicopters were banned, which of course brought some relief to those areas suffering repression after the US-incited uprising. But it also gave the Kurdish tribal leaders unfettered access to Iraqi-drilled oil wells. And so the plunder began.

Stopping a few hundred yards from the Iraqi border we watched the trucks coming over from the Iraqi state, pause momentarily, hand something over to the Turkish soldier on “border control” duty and drive on. Each lorry had an additional fuel tank welded on underneath with little clearance before the road surface. All illegal, of course, according not only to Iraqi but international and even Turkish law. It was a lonely spot for Turkish soldiers garrisoned there but no doubt a lucrative posting. And surely Turkish Government officials were taking a bigger rake-off, though nothing as crude as slipping a border guard a bribe.

After that we went to visit the Syrian border. This time it was just to see, set back a little from the road, a barbed wire fence stretching east-west. On the other side was Syria but with nothing to see there. Just for the sake of having done so, I picked up a pebble on the Turkish side and threw it over the fence – when it landed, it looked no different to the Syrian pebbles.

CARRYING CONTRABAND?

On our last evening, in the hotel in Batman, we trade unionists were taken aside and asked to carry sheets of typed paper in secret back to London. The precise nature of the content was not revealed to us but they did not contain maps or diagrams, which we confirmed with a quick riffle through them.We were disturbed and also somewhat angry and resentful, one more than the rest, who refused. Under protest, for all the good that would do me if we were searched, I agreed, distributed the papers among my belongings and said no more about it. I chose not to examine them too closely on the vague principle that the least I knew the less I could tell and to this day am not entirely sure what the contents were. Rose, having said little in the first place, packed them away quietly. I had the impression that this quiet woman was the bravest of us all, certainly of us trade unionists.

Next morning we got up at a decent hour, had breakfast and headed out to the local cafe-restaurant to kill time before we needede to head out to the airport, where waiting would be even worse than where we were.

We did not see Ghengis again but learned that he had returned home and things seemed ok. The State police must have known where he was now but had not detained him. If they questioned him he could, we supposed, say he knew nothing except the places we had asked him to go to, for which he was being paid. That would be his wisest course of action and hopefully the one he’d adopt. Hopefully too his union would exert itself to protect him.

The street being so quiet, there was little to do but chat over chai or coffee, read or look out the window. So even if we had not been somewhat nervous, it would have been difficult to miss the car that passed down the street a number of times, going first in one direction, then the other, with two men inside, wearing sunglasses.

“Political police”, I said to Arnold. He glanced out the window, nodded, returned to sipping his chai. Nobody else said anything.

At the airport, there was no sign of the plainclothes cops, only the armed Turkish airport guards and customs officials. We were processed pretty quickly and then on to the Turkish airline passenger jet, bound for Istanbul. We sat down, somewhat relieved but knew there was still the next airport to get through.

But twenty minutes later, we were still there with no sign of preparations to take off. And then there they were, the two of them coming through the plane’s forward exit, in their suits and sunglasses.

As they walked casually down the aisle towards me, I tried to empty my head and concentrate on my breathing. Tried to feel at ease so I would look it. They passed me and I did not turn my head. A little later, they passed me again heading back forward. Over the top of the passenger seat in front, I watched them as casually as I was able. They were talking to a couple of male members of the cabin crew, near the exit. About to leave? Informing them that some of their passengers were going to be arrested? Just making us sweat a bit more?

The conversation with the cabin crew was dragging on. Then a kind of wave and they ducked their heads to exit on to the stairs.

A crew member closed the hatch and dogged it securely. The engines whined, then slowly increased in pitch. The plane began to taxi, stopped, turned slowly, the engine noise increased to a roar and …. the plane jumped forward to gather take-off speed.

I heaved a sigh of relief. We were safe now, at least until our disembarkation at Istanbul. Then the flight to London and safety. Well not entirely … there would be another hurdle at Heathrow: customs. But they wouldn’t be interested in some papers, would they? British political police? Well, the very worst they could would be detention and interrogation, possible but unlikely custody, trial and sentence. The Irish in Britain were subject to the Prevention of Terrorism (sic) Act, a “temporary” suspension of civil rights introduced in 1974 and renewed annually. I had some experience of arrest and detention in Britain and, however bad it might be, I was sure there would be no close comparison with a Turkish jail. And I’d be within reach of family visits.

POSTSCRIPT

The journey back to London was without incident. I handed the “contraband” papers over to the intended recipient and that was that; phoned my family to let them know I had returned safely.

Our delegation and some of the solidarity committee arranged to meet in order to prepare our report. Rose was back on her home ground and corresponded by email, while Damien attended a few meetings. Paddy contributed his photos. Arnold and I and one other did most of the writing text, discussion and editing and in time an attractive and informative report, magazine-size with a full-colour cover was produced, featuring some of Paddy’s photos. I submitted a copy to each of my funders, sent one home, kept one and ………. None can be found now, apparently.

After reporting to my union (a brief announcement recommending the reading of the report, offering to speak at meetings and to bring other speakers, I expected to receive invitations to speak on the subject of the Kurds and the Turkish State, hopefully in support of a campaign such as a tourism boycott. No such requests came from activists in my union branch.

In all, I received one invitation to address a very small meeting in North London with which I complied and tried unsuccessfully to organise one myself in the University of London. There were no other invitations nor meetings organised by the solidarity group, which seemed to be a singular failure to capitalise on the delegation, so well organised and the report, so well produced.

I had told Arnold, once we got out of Turkey, that I thought the walk through the plane in Batman of the Turkish political police was intended as a warning to him. The rest of us had not been there before and were unlikely to return whereas he was a fairly regular visitor. I told him that the next time he visited, they would lift him. I was wrong; his next visit was with the Liberal British peer Lord Avebury, a campaigner for human rights in Turkey. But the next visit after that, without Avebury, he was arrested and spent some weeks detained in a Turkish jail before various efforts combined to have him released.

I lost contact over the years with Damien, then with Rose and eventually with Arnold too. Paddy disappeared, resurfaced, then disappeared again. There seemed little more I could do for the Kurds and in any case, had completed my course of studies and was searching for and taking up full-time employment and involved in other struggles, though I attended the occasional Kurdish solidarity public event.

In Turkey, the State’s war against the PKK has continued on and off, with the latter also varying their combat position and also reducing their demand from Kurdish independence to regional autonomy within Turkey. This position developed after 1999 when the PKK’s co-founder and leader Abdullah Ocalan was kidnapped in Kenya by the CIA and Turkish Intelligence and brought to Turkey, where his death sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment after the abolition of the death penalty. Ocalan was kept in prison on his own in an island prison until 2009 and has published articles and books from jail, among other things arguing for a “peace process” for Turkey, the delivery of which he insists requires himself set at liberty.

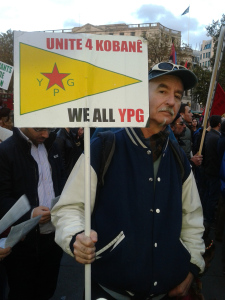

The Kurds in Syria have been the only effective force to repel ISIS (Islamic State) in the area bordering on Turkey and also rescued a great many Yazidis from the murder and rape of the ISIS fighters. Later the Kurdish armed forces there received US Coalition aid and a few years ago their commander stated in an interview that they and the Coalition were going to overthrow the Assad regime. They went on to build the nucleus of a federal administration defended by their fighters (reputedly about 40% of which are female). Turkey attacked Kurdish cross-border traffic (supplies, recruits) but more recently invaded Syria ostensibly to support the jihadist anti-Assad forces that they support but more seriously to attack the Kurdish YPG, which they consider an offshoot of the PKK. Assad is unlikely to agree to their autonomy, even the US seema ready to drop them and the future looks dark for the Kurdish forces there.

In Iraq the Kurdish movement, mainly organised tribally originally, split into war-bands during the Second Iraq War fighting alongside the US Coalition forces. They took part in the plunder of Iraqi non-Kurdish areas, including Baghdad, along with other forces and shootouts between different warbands were not unknown. The Kurds have their oil-rich area protected within Iraq but the overall administration of Iraq is a US-dependent puppet regime and very unstable.

In Iran, suppression of Kurdish national identity continues under the religious regime.

The Kurds continue their struggle, the largest nation without a state.

FOOTNOTES:

LINKS FOR REFERENCES AND FURTHER INFORMATION

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_Kurdistan

Kurdish Republic 1923: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurdistansky_Uyezd

Kurdish Republic 1946: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_of_Mahabad

Iraq regime chemical attack on Kurds: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/halabja-the-massacre-the-west-tried-to-ignore-qsl8n6nspc7

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halabja_chemical_attack

http://kurdistan.org/turkeys-kurdish-policy-in-the-nineties/

Armed conflict between Turkish state and Kurdish resistance:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurdish%E2%80%93Turkish_conflict_(1978%E2%80%93present)

Istanbul monument: https://medium.com/stories-to-imagine/horses-a-column-the-battle-that-changed-the-world-12aa3604067f

Kurdish elected representative detained unreasonable length of time: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/11/european-court-orders-release-kurdish-politician-demirtas-181120093432466.html

Ancient and Old

https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/indepth/2018/2/5/the-quest-for-identity-how-kurds-are-rediscovering-zoroastrianism

Hasankeyf archaelogical site threatened: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasankeyf#Archeological_sites

Yoruks (nomads): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y%C3%B6r%C3%BCks

Synopsis of the story of the star-crossed lovers: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mem_and_Zin?fbclid=IwAR2K7umXF41Awt0wwo6lbZXVB-3KIRY8AUwu7Wow5U477oJyYMwuoNbZZ2E

.jpg)