By Shakhawan Shorash:

There are many accounts of mass killings, ethnic cleansing, and genocide against defenseless minorities committed by state authorities and military forces in the multiethnic states in the twentieth century. Long term ethnic tensions and conflicts during the colonial period and after the end of colonialism continued in many countries, including Turkey, Iraq, Sudan, Rwanda, Nigeria, Indonesia, Cambodia etc. These resulted in mass killings and destruction campaigns committed by the states at different times. Ethnic conflict and the factors behind the conflict make the risk of mass killings and genocide higher and more possible in multiethnic states. Ethnic conflict factors have the ability to promote a genocidal mentality and can result in the crime of genocide when extreme leaders and ideologies take political and military power.

The tension between the oppressed Kurds and the Turks goes back to the nineteen century under the Ottoman Empire and continued after the birth of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. In Turkey, close to the end of the Ottoman Empire, there were many internal, negative factors at play, including legitimacy problems, weak national identity, internal security concerns, demographic changes and bias, the dominance of an ethnic mosaic and multiethnicity inside the country, border problems, discrimination, marginalization, historical injustice, exclusionary ideas and leaders, secession trends, and external concerns. In response to these internal problems, which weakened the Ottoman Empire, some radical nationalist groups emerged. The extant negative factors created a suitable ground for the rise of Turkish radical nationalism, which developed and progressed quickly and created the right circumstances for the elevation of a rigid and intolerant mindset toward non-Turkish minorities. The nationalist political organization Itihad u Teraqi (Committee of Union and Progress) and young Turkish officers and the thinkers, such as Ziya Gokalp the author of The Principles of Turkism, influenced the Turkish society. The nationalist trend focused on the creation of a strong Turkish national state based on Turkish identity.

The extreme nationalist movement, which focused on Turkishness, laid the groundwork for the promotion of genocidal factors, such as dehumanization of the unwanted ethnic groups and rationalization of the ethno-nationalist genocidal aims. Non-Turkish ethnic groups rejected the rigid Turkish nationalist mentality and continued to support the plurality and multiethnicity of the society. However, according to Turkish nationalism, those ethnic groups could not fit into a national Turkish state, as they constituted a serious problem for Turkish national identity and were a real threat to Turkish unity and sovereignty. Therefore, they were unwanted, and Turkish nationalism legitimized the ultimate solution—the cleansing of Turkish society of the impure ethnic elements via expulsion, assimilation, ethnic cleansing, or genocide. The unwanted ethnic groups were the Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, Kurds, Qizikbash, and other small ethnic groups.

When the radical nationalist group took control and had authority over the military power and resources, the realization of ethnic cleansing and genocidal aims became likely. This nationalist government of The Young Turks, wiped the Armenians out in an organized and systematic destruction campaign in 1915. Nevertheless, the genocide of the Armenians was not the last destruction campaign committed by Turkish ethno-nationalist leaders. In fact, Turkish nationalists cleansed the country of non-Muslim ethnic groups of Greeks, Assyrians, Qzilbash (Shia-Muslims), and Ezidi Kurds.

In 1923 Mustafa Kamal, the founder of the new Turkey, took power as the first Turkish president of the Republic of Turkey. He too was an extreme nationalist, inspired by the Young Turks and nationalist thinkers. Like the other nationalist officers, he believed in a pure Turkish ethnic state. He and three other officers established the political organization called Motherland and Freedom in 1905, and, in 1908, he was among the first members of the nationalist organization of Itihad u Teraqi. Thus, the extreme nationalist wave continued its power after the birth of the new Turkey.

Turkish leaders had another policy concerning the Kurds in general and the Alevi Kurds of Dersim in particular. Turkish leaders, especially Mustafa Kamal, used the loyal Kurds in the independence wars against the Greeks and the Armenians in exchange for political rights (Beshikchi, p. 3). Mustafa Kamal was aware of Kurdish separatist tendencies and this policy aimed at weakening the Kurdish resistance. Mustafa Kamal stressed Kurdish-Turkish unity and regarded the Kurds as brothers and the Turks and Kurds as an undivided people. In September 1919, he stated: “Turks and Kurds will continue to live together as brothers around the institution of khilafa, and an unshakable iron tower will be raised against internal and external enemies.” When the Ankara authority under the leadership of Mustafa Kamal became stronger in 1921, he removed the Kurds in his statement:

There is only one kind of nation within these borders. There are Turks, Circassians and various Muslim elements within these borders. It is the national border of brother nations whose interests and aims are entirely united . . . God willing after saving our existence this will be solved among brothers and will be dealt with. (Cited in McDowall, 2000, p. 188).

According to Turkish nationalism “Kamalism”, Turkish leaders had to deal with non-Turkish Muslim elements in society, and the approach taken was to assimilate these Muslim elements into Turkish society. As Ziya Golkalp, the Turkish nationalist thinker, stated:

A nation is not a racial or ethnic or geographic or political or volitional group but one composed of individuals who share a common language, religion, morality or aesthetics, that is to say, who have received the same education”. (Cited in McDowall, 2000, p. 189).

It is worth remembering that the Treaty of Sevres in 1920 gave the Kurds and the Armenians the right to establish their own states in Southeast Turkey (see Appendix 3). That strengthened the Kurdish hope for independence from Turkey, but when the Lausanne Treaty in 1923 removed the promises of a Kurdish state in Southeast Turkey, the division of Kurdistan between the regional states became a reality. Thus, the League of Nations and the colonial powers of United Kingdom and France followed colonial interests and ignored the Kurds. Turkey came out of the Lausanne Treaty as a winner. It then focused on the building of a homogeneous Turkish national state.

Turkish leaders waited for the right time to deal with the Kurds. Soon, the government removed Kurdish officials form important government and administrant posts and replaced them with Turks. A comprehensive program of Turkification of the non-Turkish elements was activated in schools and other public places. At the same time, the government started to systematically erase Kurdish and other unwanted languages and cultural elements. Turkey also passed resettlement laws regarding the Kurds. The aim was the assimilation of the Kurds in Turkish society. Thus, Mustafa Kamal did not only run away from the promises he gave to the Kurds, he would cleanse the Kurds in the Turkish society entirely by assimilation and elimination. Turkey began to neglect the existence of the Kurds and Kurdish language in Turkey. Ismail Beshikchi writes in ‘Genocide in Dersim’:

“Contrary to promises made during the war, the existence of Kurds and Kurdish language was denied. Towards the end of 1922, Kurds and Kurdish language were neglected and ignored. Denial and annihilation, Turkification and assimilation of the Kurds to Turkishness remained a fundamental state policy.”(Beshikchi, p. 16)

Kurdish reaction against this policy came in the guise of short revolts and weaponry resistances against Turkey during 1920s and the first half of 1930s. The Turks took a harsh military stance in response, involving the destruction of Kurdish villages, mass deportations, and mass executions. In this particular period, tens of thousands of Kurds fled their homeland forever and went to neighboring countries. The Turkish government established two tribunals called Tribunal of Independence: one in Ankara and one in the east of the country in the spring of 1925. The eastern tribunal was authorized to apply capital punishment. Under the Law for the Restoration of Order, the Government justified the punishment of people. According to the law, in the event of revolt, instigation, publications, or any sort of actions that led directly to trouble, the order or social harmony could be brought before the tribunal (McDowall, 2000, p. 195).

In connection with Turkey’s response to a revolt in the town of Bitlis in 1927, the British ambassador Sir George Clerk wrote:

To transport from the Eastern Vilayets an indefinite number of Kurds or other elements . . . the government has already begun to apply to the Kurdish elements . . . the Policy which so successfully disposed of the Armenian minority in 1915. It is a curious trick of fate that the Kurds, who were the principal agent employed for the deportation of Armenians, should be in danger of suffering the same fate as the Armenians only twelve years later. (Cited in McDowall, 2000, p. 199).

However, the escalation of the internal ethnic conflict resulted in a cruel reaction against the Kurdish society in Southeast Turkey and launched an eradication policy against core groups of Kurds. In order to implement the ethnic cleansing policy in the Kurdish territory, the state created four Inspectorate Generals to govern Kurdistan, which were supported by the Legislation numbered 1164 in June 1927. The First Inspectorate-General was established in November 1927, and the Fourth Inspectorate General was established on January 6, 1936 following the acceptance of the Tunceli Act dated December 15, 1935 (see Beshikchi, p. 18).

The Kurds from the Dersim region, which is located in a strategic place in the east of Anatolia, frequently were in conflict with the Ottomans. The Ottomans and the later nationalist government of Ankara could not control the region as they wished, and they were worried about the nature of the disobedience of the region, the destiny of the region due to Kurdish-Armenian relations, and the harm it could do to Turkish national interests and the unity of the country. The region also included the promised Kurdish state, which had been determined in the Treaty of Sevres in 1920. The Dersim region was subject to many military offenses by the Ottomans (see Dogan, p. 52-77). Consequently, Turkish leaders wanted to control the region at any price due to its importance for Turkey.

What made Dersim peculiar and the Turkish genocidal policy a priority was that the Kurdish people of Dersim were significant in the struggle for Kurdish freedom. Dersim Kurds launched a number of uprisings against the Turks before and after the end of the Ottoman Empire. The people of Dersim were Alevi Muslim (Shia Muslims) that were unwanted in Turkish nationalism. The people of Dersim also helped the Armenians to escape the mass killings committed by the Young Turks’ government. Turkish forces could never totally quell Dersim. Thus, Turkey did not trust the people of Dersim and would not restrain itself in its assimilation policy. Turkey intended to destroy the people of Dersim.

The dehumanization of the Dersim people can be found in the transcripts of meetings and talks of Turkish leaders. Nuri Dersimi, a civil servant relates that in a meeting in May 1930, Deli Fahri (provincial governor of Elazig) said:

“The laws . . . damn them. Every word uttered between our lips is law. The Turkish nation does not expect any form of service from the Dersimites, whether material or moral, events have confirmed this conviction of the Turks to be true . . . For the past five years, the Dersimites have provided assistance and shelter to the armed Kurdish gangs . . . . Deli Fahri raised his hands and pulled a hair out of his head and said “This is Dersim, Dersim . . . My head before your eyes is the Republic of Turkey. When I pulled the hair out did I exert any force? By pulling out my hair did my head suffer any harm? Did my head lose anything?” (Beshikchi, p. 19-26)

A statement made by the head of general staff, Marshall Fevzi Cakmak, stressed the dangers posed by the Alevists, Kurdish bandits, and Kurdish civil servants to the Turkish community through the “Kurdifying” of Turkish villages, the spreading of the Kurdish language in Turkey, and the risk of invasion of Erzincan Province (Beshikchi, p 13). The term “Kurdish bandits” was widespread among Turkish leaders before and after the birth of the Republic of Turkey, as Kurdish resistance for freedom was interpreted as banditry.

Turkish leader Hamdi Bey (from the civil services inspectorate) wrote in his report on February 2, 1926:

Dersim is a carbuncle for the government of the Republic. To operate on this carbuncle and prevent the possibility of pain is a must for the salvation of the nation . . . To build schools, construct roads, in order to provide means of prosperity to build factories, to provide a variety of industrial jobs and work to keep them occupied or to try and progress them through settlement and civilization is nothing but an impossible fantasy . . . It is necessary to settle Turks on lands to be ploughed . . . Once this rehabilitation is complete, to appoint idealist elements as public servants for a term of twenty five year, given the missionary roles with a view to Turkify the Kurds in the region. (see Dogan, p 89)

In continuation of the assimilation of non-Turkish elements, the government deigned territorial zones for areas inhabited by non-Turkish ethnic groups with non-Turkish culture. People in regions such as Dersim were to be removed completely.

The Turkish state’s move against the Dersim people started after the Resettlement Law of 1934. In 1936, the name of Dersim was changed to Tunceli, and the government considered Tunceli as a pure Turkish region with purely Turkish residents. Thus, a siege began and a new military governor, General Abd Allah Alp Dogan, was appointed. In early 1937, thousands of troops gathered around the Dersim region. Not unexpectedly, the people of Dersim were against the policy of compulsory deportation and assimilation into Turkish society (McDowall, 2000, p. 208).

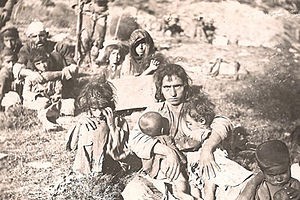

In 1937, the Kurdish leaders in Dersim sent emissaries and pleaded with the Turkish military governor to be allowed to stay in their homes and administer themselves, but the governor refused their demand and killed the Dersim representatives. The Kurds responded with an ambush of Turkish soldiers. The Turkish military began a series of brutal and comprehensive attacks on Dersim Province with genocidal intent. The destruction of Dersim’s Kurds was a replication of the Armenian genocide in 1915. Some of the same killing methods were used. The army destroyed and burned down Kurdish villages, arrested men, women, and children in the villages and deported them to unknown destinies. Ill-treatment and torture and rape of women and girls was widespread. Families that escaped the villages and hid in caves were attacked with chemical weapons and were killed en masse. Those who tried to bring water and food to their family members and children or desperately fled the caves because of thirst and hunger or chemical attacks were attacked and killed. Referring to Social Engineering in Eastern Anatolia Dersim-Sasun (1934-1946),p. 419, Beshikchi cites:

Methods used included the forced suppression of the caves, firearms, burning of wood and sulphur in front cave openings in order to make breathing difficult for those inside, or in cases where these measures failed to impact, cause the caves collapse with demolition blocks. Demolition blocks were not used in some cases where the caves were located in between high and solid rocks. In these cases it was necessary to ensure that those inside were condemned to starvation and thirst. All of these situations were encountered and necessary measures were used with a view to capturing those inside. All caves discovered throughout the operations were, without exception, penetrated. (Beshikchi, p. 30)

Said Raza, the leader of the Dersim people, and some of his fellow leaders were forced to surrender and were executed immediately. The killing and destruction ended in the fall of 1938; tens of thousands of the Dersim people were killed or disappeared. According to Kurdish sources such as Kurdish PEN, the number of the victims is more than 50,000. According to British sources, the number is around 40,000 (McDowall, 2000, p. 209). However, the destruction happened systematically and was legalized by the law of resettlement and assimilation of non-Turkish people. The destruction was intentional, and it destroyed more than half if not most of the Dersim people.

Further reading

Beshikchi, Ismail, 1992, The Tunceli Act (1935) and Dersim Genocide (1937-38), Yurt Books-Publications.

Van Bruinessen, Martin, 1994, Genocide in Kurdistna? The supression of the Dersim rebellion in Turkey (1937-1938) and the chemical war against the Iraqi Kurds (1988), in George J. Andreopoulos (ed), Conceptual and historical dimensions of genocide. Unversity of Pennsylvania Press, 1994, pp. 141-170.

Cengiz, Seyfi, 2005, DERSIM/ZAZANA – AN INTERNAL COLONY OF THE TURKISH STATE

Dogan, Erdal & Eren Keskin, 2012, The Dersim Genocide and Ongoing Cultural Genocide. In The Dersim Massacre 2013 by Ali Mahmud and Shakhawan Shorash (ed).

KILIÇ ABDULLAH & AYÇA ÖRER, 2011, The Upper Echelons of the State in Dersim, available at http://www.timdrayton.com/a55.html

Mango, Andrew, 2004, Atatürk, London.

Mahmud, Ali & Shakhawan Shorash (ed), 2013, The Dersim Massacre, Erbil.

McDowall, David, 2000, A Modern History of the Kurds.

White, Paul 2006, Ethnic Differention omong the Kurd: Kurmancî, Kizilbash and Zaza

Wikipedia, The Dersim rebellion, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dersim_rebellion

Kieser, Hans-Lukas, 2012, Case Study: Dersim Massacre, 1937-1938, available at Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence: http://www.massviolence.org/Dersim-Massacre-1937-1938

Shorash, Shakhawan, November 2011, Erdogan´s apology between recognition and denial, available at http://kadirshorsh.com/?p=416

This article is published as the introduction to ‘The Dersim Massacre’, published in Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2013.

Shakhawan Shorash was born in Hawler in Southern Kurdistan. He is a freelance writer with a BA in political science from Southern University of Denmark (Odense) and a Masters degree in political science from the University of Copenhagen.

.jpg)

Thanks for this article, we the commitee Kurdistan Free! write about the genocide in Dersim in our second book On the road to Kurdistan, will be published in the fall of 2015. The world must know this!

There are certain Foreign Interest Groups furthering their own countries hidden agendas in South incite chaos . There shall be no more wars waged by War of Independence. 50 Million Kurds have not yet gained their rights peacefully. Independence in South is the only solution. Goodbye Obamas Admin and Baghdad.