By Dr Kamal Mirawdeli:

‘Love and Existence: Analytical Study of Ahmadi Khani’s Tragedy of Mem û Zîn’

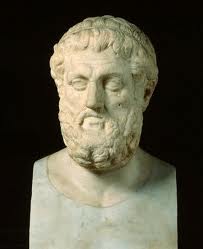

Part III, Chapter 2: Aristotle’s theory of tragedy

Poetry and tragedy

For Aristotle, a fundamental premise that defines what is being a human is that “All human beings by nature desire knowledge” (Metaphysics, (980a1). Therefore they do not only know, but they also know or try to know why and how they know and do certain things. This specific human ability Aristotle calls tekhne. He defines this term as “a productive capacity informed by its intrinsic rationale“ (Heath, 1996, p. ix).

The production of poems too can be a tekhne as ‘an activity with its own intrinsic rationale, and it can be rendered intelligible’ (ibid., p.x) although the poets themselves may not be aware of their tekhne or instruments and technics they have used. For poetry can be produced as a result of instinct or talent as well as conscious construction. Poets must be able to project themselves onto the emotions of others; natural talent, or even a touch of insanity, are necessary for this (Poetics, 55a30-4).

Also ability to produce metaphor, which is for Aristotle the most important feature of poetic language, depends on having a natural gift to perceive similarities, something that cannot be taught. But once poetry is produced, it is possible to understand what makes a poem good. Poetry has always excited the wonder, which Aristotle sees as the root of philosophical enquiry. Therefore by trying to understand poetry we can fulfill our human desire for knowledge and enhance the pleasure we derive from the wonder of poetical discoveries, beauty of language and power of melody. Poetry, for Aristotle, is a natural human activity which engages a number of human instincts such as those for imitation, rhythm and melody.

Poets are likely over time to discover better and better ways of doing it, if only by experiment; thus tragic poets (in Aristotle’s view) found the best kind of tragic plot by trial and error. (54a9-12) For Aristotle, poetry is better if it has a structured plot and if its mode is dramatic rather than narrative. For poetry, as imitation, creates greater likeness if the words of those involved in the action are presented directly rather than being mediated by a narrator (Ibid.p. xvii). “Homer was the outstanding poet of the serious kind, since he did not just compose well but also made his imitations dramatic.” (3.2)

Thus, Aristotle’s Poetics “concentrates on tragedy, the most highly developed form of poetry concerned with superior persons. Epic is given relatively brief treatment as a pendant of tragedy” (Ibid. xviii).

Generic definition

The problem of generic definition of works of art we mentioned earlier is in fact the first issue that is dealt with by Aristotle in his Poetics. Aristotle opposes generic definition of a work based on its formalistic features. He criticizes those who recognize poetry as verse –form or verse-form as poetry. “People attach poetry to the name of the verse-form, and thus refer to ‘elegiac poets’ and hexameter poets’; i.e they do not call people ‘poets’ because they produce imitations, but indiscriminately on the basis of their use of verse.” (47b). While Homer is a poet, Empedocles is not ‘having nothing in common except form of verse they use.; so it would be fair to call the former a poet, but the latter a natural scientist rather than a poet” (47b) Also ‘the historian and the poet are not distinguished by their use of verse or prose” but by the fact that “the function of the poet is not to say what has happened, but to say the kind of thing that would happen, i.e, what is possible in accordance with probability or necessity “(5.51b).

Tragedy and epic

Although tragedy and epic have a lot of common but still they are different since “anything that epic poetry has is also present in tragedy but what is present in tragedy is not all in epic poetry” (3.5). “Epic poetry corresponds to tragedy in so far it is an imitation in verse of admirable people but they differ in that epic uses one verse-form alone and is narrative”. Epic is also “unrestricted in time, and differs in this respect” (3.5) by making its plot different. Given the primary importance Aristotle gives to plot, his explanation of what differentiates tragedy from epic is focused on the structure of plot. In epic, as in tragedy, the plot should be unified, with a beginning, middle, and end suitably connected. But as epic is unrestricted in time and the number of actions it imitates, it makes it hard to grasp the plot as a whole. Epic also mostly uses narrative rather than direct dramatic language and allows irrationalities to be part of the plot while this should not happen in the tragedy. Also tragedy is superior to epic because it is more concentrated; pleasure is better concentrated than spread thinly (62b1-3). (Also see: Heath, pp.liv-lxi).

Elements of tragedy

Aristotle first offers a general definition of tragedy and then explains its component parts. “Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is admirable, complete and possesses magnitude; in language made pleasurable, each of its species separated in different parts, performed by actors, not through narration; effecting through pity and fear the purification of such emotions” (4.1.6). Aristotle further explains the main elements of tragedy: “So tragedy as a whole necessarily has six component parts, which determine the tragedy’s quality; i.e. plot, character, diction, reasoning, spectacle and lyric poetry”(4.250a).

Starting from this general definition, Aristotle stresses from the very start that tragedy is the imitation or recreation “not of persons but of actions and of life” (4.3i). Therefore it necessarily has these constituent elements:

- Plot, which is the ordered sequence of events, which make up the action being recreated. “The plot is the source and the soul of tragedy: character is second”, because ”Well-being and ill-being reside in action, and the goal of life is an activity. Character is included along with and on account of the actions. So the events, i.e. the plot, are what tragedy is there for” (4.3.i).

- An action is performed by agents and agents necessarily have moral and intellectual characteristics, expressed in what they do and say. From this we can deduce that character (moral disposition) and reasoning will also be constituent parts of tragedy.

- “Character is the kind of thing which discloses the nature of a choice.” While “Reasoning is the ability to say what is implicit in a situation and appropriate to it. Reasoning refers to the means by which people argue that something is or is not the case, put forward some universal proposition” (4.4.50b).

- Plot, character and reasoning relate to the object of tragic recreation. The medium of tragedy is rhythmical language, sometimes on its own and sometimes combined with melody. This gives us further two constituents of tragedy; diction and lyric poetry.

- Tragedy is poetic recreation in the dramatic mode. It is designed to be acted out on-stage, where the action (unlike the action of an epic) can be seen. So tragedy also includes spectacle, everything that is visible on stage. Epic is more tolerant of irrationality because the action is narrated but not seen, but the poet needs to visualize the tragic action. There should not be any irrationality in the action, but if there is it should be outside the play (51a1-6). ((bid. Lvi-Lvii).

- But the tragedy is ultimately a poem, not a performance. A tragedy, which for whatever reason, is never performed is no less a tragedy. Spectacle is a part of tragedy in the sense that tragedy (unlike epic) is potentially performable. The effect of tragedy is not dependent on performance and actors” (4.4 50b).

- Tragic mode is the result of actions and events and is not determined by character or moral intentions and dispositions. We can speak of success and failure only in relation to someone’s exercise of his abilities, in relation to praxis, action not just in the sense of what someone does but also in the sense of how they fare.

- Success and failure depend on action. And by imitating this action tragedy effects through pity and fear the purification of such emotions (49b27f). Katharsis aims to excite a response of pity and fear. Tragedy is a ‘recreation of events that evoke fear and pity.” (52a2f).

- “So Aristotle’s first argument for the primacy of plot is as follows: tragedy aims to excite fear and pity; these emotions are responses to success and failure; success and failure depend on action; hence action is the most essential thing in tragedy; therefore plot is the most important element (Ibid. p. xxi). Knowledge of an individual’s character is not essential to an understanding of their actions (Ibid. pxxii).

Tragedy and dramatic plot

- Tragedy, for Aristotle, is an imitation (recreation) of an action that is complete and has magnitude (Ch. 6 & 7 of Poetics). Completeness means it is a whole that has beginning, middle and end” (50b26f). This means the action is not random but there is necessary inner interconnectedness or ordered structure in the sequence of the events. “First, the plot consists of a connected series of events: one thing follows on another as a necessary consequence. Secondly, the plot consists of a self-contained series of events” (Ibid.pxxiii).

- Plot and text are distinct. Plot is therefore not co-extensive with the play (Ibid.pxxiv).

- In terms of magnitude, the lower limit is determined by the need for the plot to include a change from bad fortune to good fortune, or from good to bad. The plot must have sufficient scope for such a change to take place, “a series of events occurring sequentially in accordance with probability or necessity gives rise to a change from good fortune to bad fortune, or from bad fortune to good fortune, is an adequate definition of magnitude” (5.251a). Tragedy involves suffering, which is an “an action that involves destruction and pain” (52b11f).

- An imitation is unified if it imitates a single action or object. If tragic plot involves a change of fortune, the single action will inevitably include a series of events. These must be a self-contained series of connected events). The plot is simple if the action is unified and continues without reversal or recognition. It is complex if the change of fortune involves reversal or recognition or both. “These must arise from the actual structure of the plot, so that they come about as a result of what has happened before, out of necessity or in accordance with probability. There is an importance difference between a set of events happening because of certain other events and after certain other events” (6.2-10).

- If a plot consists of complication and resolution, the two stages of a plot hinging on the change of fortune, then excellence in plot-construction must embrace both parts. Resolution should arise from the plot (54a37f). That is the poet should put together a sequence of events in which the change of fortune and its consequence are a necessary or probable consequence of everything that has gone before (Ibid. Lii, Liii).

- Poetry also “tends to express universals” (51b6f). The universality of poetry gives it something common with philosophy. But while philosophy is directly concerned with universal truths, poetry’s concerns are indirect; the universality of poetry is a by-product of its aim to construct effective plots (Ibid. xxvii-xxviii). Poetry is more philosophical and more serious than history. Poetry tends to express universals, and history particulars” (5.5.51b).

- Tragedy is “an imitation not just of a complete action but also of events that evoke fear and pity” (52a1-30). The best kind of tragic plot is the one which is most effective in arousing pity and fear (Ibid. pxxxi). A tragic plot is more likely to evoke fear and pity if a person inflicts harm on a philos, someone close to them (ibid. p. xxxiii) A tragedy is an imitation of an action that is admirable (48a2).

Characters of tragedy

- Character is imitated when what is said or (presumably) done reveals the nature of the choice that is made, and hence the underlying moral disposition of the person who is speaking or acting. So, when Aristotle talks about character he is not talking about the quirks and details of someone’s individuality, but about the structure of their moral disposition so far as it becomes clear through what they say and do (Heath, ibid. p.xliii).

- Tragedy is essentially concerned with people of high status and good moral character; there will be peripheral figures (slaves and so forth) of lower status, but they cannot be at the centre of tragedy’s interest and should at least be good of their kind. Tragedy is usually concerned with people better than we are, but it can also be concerned with people like ourselves (ibid. p. xlv).

- Character and reasoning are two bases of action. Reasoning includes elements of assertion; denial, generalisation, and speech in which characters arouse emotion or make things look important or unimportant. That is all ways in which, in a tragedy, one person can use language to influence another.

- A tragedy aims to excite pity and fear, so a story is needed that will have a powerful emotional effect; we know from discussions in chapters 13 and 14, that, for Aristotle, Greek mythology is a rich repertoire of such stories, so it makes sense to return there to find a suitable subject (Ibid. p. xlix).

General conclusion

Tragedy is the dramatization of an event, action or character chosen from the past mythical or folk tradition, which imitates or reflects an important aspect of human life. The most important element in tragedy is the recreation of life and its events, actions and agents. Therefore plot is the most important primary component part of any tragedy. Plot is the organization of the sequence of the events in the text, which must have a unified structure, that is, having a beginning, middle and end, structured not by the mechanical sequence of time but by the factors of necessity and probability. Characters are what they are on the account of the actions they take and the choices they make. Tragedy imitates admirable actions and includes suffering and the rise and fall of good and bad characters.

The most successful dramatic plot is the one that evokes greatest pity and fear and, by doing so, giving the reader or spectator pleasure of katharsis, purification of such emotions and recreating a balance in their own psychological life. As tragedy is poetry and poetry is the recreation of life as it would be, using also dramatic language instead of narrative, making use of metaphor, music and dialogue, tragedy, as a verbal art, is the highest form that poetic expression can take, it is even higher than epic and close to philosophy.

It is the works and trials and experiences of tragedy- writing of great classical poets that allowed Aristotle to define the structural rules and dramatic modes of tragedy and not otherwise. Therefore, no genuine work of tragedy can be judged by rigid pre-existing standards and formal criteria. Each work expresses its unique individuality through its own inherent strategies, structures and mode of existence and expression. In other words, although the traditional defining elements and formal features of tragedy are quite helpful in identifying the framework and structure of a work of tragedy, it is the individualistic uniqueness of the work itself that ultimately defines it as a work of art.

* ‘Love and Existence: Analytical Study of Ahmadi Khani’s Tragedy of Mem û Zîn’ by Dr Kamal Mirawdeli is published by the Khani Academy in association with authorhouse, uk. The hard cover, soft cover, or the electronic edition of the book can be ordered from: http://www.authorhouse.co.uk/Bookstore/BookDetail.aspx?Book=419087

- See all the extracts to date

.jpg)