By Amy L. Beam, Ed.D:

“If it were not for the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) helping us all along the way, there would not be one Ezidi left alive today.” This was the same litany I heard repeated from dozens of refugees in camps in Roboski, Hilal, and Şirnak, in North Kurdistan (southeast Turkey).

When I visited the Shengal (Şingale or Sinjar) refugee camp at the school in Roboski, on Sept. 3, the first person I met was 24-year-old Shekh Alyas who introduced himself as the camp translator. He speaks four languages and used to work for the U.S. Army as a translator. He is an environmental safety specialist and was vice president of a company before the ‘Islamic State’ terrorized his region and disrupted his life.

Alyas spent five hours translating as I listened to dozens of tragic stories from people who have been running for their lives since August 3 and 4, 2014, when the ‘Islamic State’ forces (also known as IS, ISIS, or ISID) attacked Ezidis living in Shengal in northwest Iraq on the border of Syria.

ISIS entered Shengal villages threatening and shooting people. Some were beheaded to heighten the sense of terror. Many men, women, and teenage girls were kidnapped with females being sold for sex. Residents fled to the nearby mountain range on foot. Some left with only a five-minute warning. ISIS forces surrounded the Shengal region, trapping people on the mountain top for over one week without food or water. Many died of dehydration. At least one person died from a scorpion bite.

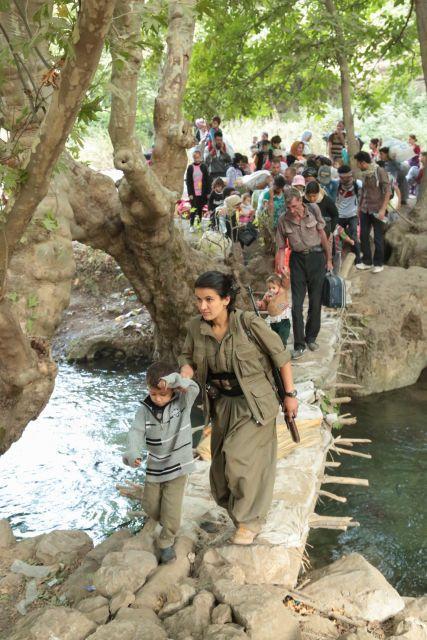

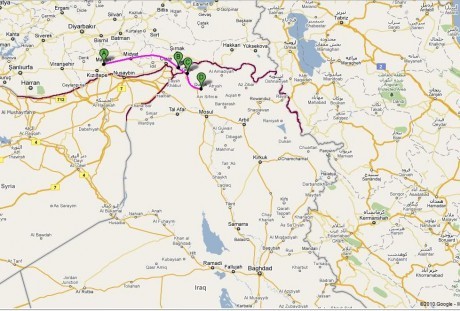

The Kurdish guerilla forces of PKK (from Turkey) and YPG (from Syria) opened a route from Shengal to Syria on August 12 for people to escape ISIS by car and on foot. The people I interviewed were adamant that no one else helped them.

When the PKK broke through the ISIS forces, 14 family members of my translator’s family miraculously jammed into his father’s Opal and drove east one hour to the Syrian border. A friend informed him by phone that ISIS had stolen all valuables from the empty houses and Alyas’ family house had been burned.

From Syria, Alyas’ family drove seven hours northeast to Duhok, then Zakho in northern Iraq where they abandoned their car. The PKK also controlled this route from Syria and offered food and water along the way. They spent 12 days sleeping in a school in Zakho while deciding what to do.

Someone offered to take Alyas’ family to the border of Turkey for $400 US dollars. Being poor, they declined this offer and finally accepted a ride on a pickup truck filled with four families. Each family paid a driver $100 dollars for the 40-minute drive into the mountain north of Zakho.

The driver turned them over to the care of a uniformed PKK guerilla who then guided them on foot to a PKK camp in the mountain where they slept two nights. The PKK provided food, water, blankets and pillows while refusing all money.

Every family in Roboski, Turkey, owns at least two or three horses. These horses are traditionally used for their border trading which Turkey calls smuggling. All Roboski families sacrificed by diverting the use of their horses from trading to meet the refugees each morning at the unguarded border on the mountain ridge above their village.

The Turkish government, for its part, withdrew soldiers from the mountain border and did not interfere with the flow of refugees.

The weak and elderly were transported by horse or car to the Roboski school where everyone was fed and sheltered for one or two nights before being transported to another refugee camp to make room for the next wave of people arriving from the PKK camp in South Kurdistan, Iraq.

Alyas’ family of 15 and his uncle’s family of 10 walked from the PKK camp so as not to be separated. It took them 9 hours to reach Roboski which has a population of 1200 people comprising only 160 families.

When the Ezidi refugees in the Roboski school camp heard about the CNN Turk TV report last week that the PKK was charging each person money to cross the border into Turkey, they were indignant. I asked a hundred people in camps in three different towns if they had heard of anyone paying the PKK for their assistance. Everyone was adamant that the PKK refused money and that, if it were not for the PKK, they might be dead.

According to Roboski community leader Ferhat Encu, Roboski has welcomed, fed, and sheltered 20,000 Ezidis in one month. Nearby villages of Gulyazi, Yemişli, and others sheltered another 4,000 people. Hikmet “Reber” Alma (Twitter @reberalma) led the aid effort in Gulyazi. Roboski and Gulyazi people know what it is like to be deeply wounded.

Ferhat Encu is the spokesman for the Roboski family survivors of the infamous Roboski massacre on Dec. 28, 2011. The U.S. flew the drone and then passed the location to Turkey which flew two F-16s and killed 34 innocent men and boys carrying petrol on their mules over the mountain ridge from Iraq (South Kurdistan) to Turkey (North Kurdistan).

Turkey falsely claimed that a PKK general was the target. The government called it an operational mistake but offered no apology. The Roboski families have appealed their case against the government in a military court in Ankara and are awaiting a decision.

As the first Ezidi refugees arrived in Roboski, the local Kurds immediately opened their hearts and school to them. The trickle of 20 people on the first day grew rapidly to 4,000 people arriving on Sept 1, and 1,300 arriving on Sept 2. To manage the turn-over, each group of people was fed and allowed to spend one or two nights before being sent by bus to camps in Şenoba, Şirnak, Cizre, Silopi, Batman, Siirt, and Diyarbakir. Then the next group of arrivals would be sent from the PKK camp in Kurdistan, Iraq to Roboski.

The Roboski camp is managed on a volunteer basis by Lezgin Encu and Ferhat Encu with the assistance of the community and the refugees themselves. There are no white tents labeled with “UNHCR” (United Nations High Commission on Refugees). No representatives from Ankara, Europe or the International Red Cross showed up. According to camp leaders, no money has been provided by Ankara or international aid agencies for the relief effort.

When one has a history of persecution and forced dislocation and has learned that no one is coming to the rescue, one does not wait to move into action. This humanitarian aid effort is entirely managed through the generosity of Kurdish families and friends in Turkey and world-wide. In every Kurdish town and city, the Kurdish DBP party (formerly BDP) set up tents to collect goods and money for the refugees and forwarded it to local Kurdish municipalities (Belediyesi).

In Roboski, the owner of a new building under construction donated one floor as a warehouse for blankets, carpets, pillows, clothing, dry goods, and food. It is piled high with bags of rice, macaroni, beans, flour, and sugar all purchased by Kurdish donations.

To manage the movement of people, all Kurdish towns have provided their public city buses to transport refugees from one town on to the next town in order to accommodate new arrivals. Every school in southeast Turkey is used as a refugee camp.

On September 4, the tents at Roboski school were taken down and the school parking lot cleaned in preparation for school to begin. Alyas was lucky to be in the last group of Ezidis to arrive to Roboski. The next group of 1,500 was taken directly from Roboski border to Sirnak on Sept. 7.

As the school refugee camps are closed in order to open for the new school year, the need is now urgent for both the Turkish parliament, the United States, and European Union members to address the issue of resettlement. Shengal was the historic homeland for over 700,000 Ezidis.

They are now homeless and insist they can never return to Iraq to live without fear. Every refugee I spoke with insisted he wanted to continue on to Europe or elsewhere. There is nothing to return to.

Will the Ezidis, as a people, simply cease to exist or will governments of the world open their doors to them? It is now a political question which requires intervention by federal governments and the United Nations.

How You Can Help:

- Contact United Nations, European Union, parliament members, aid organizations, and media outlets.

- You can also do as this writer did: get in your car and show up at one of the refugee camps. You will be welcomed. Do not wait for some agency to endow you with power. Every individual has the innate power to take positive action or help even one individual or family.

- Ferhat Encu @ferhatencu on Twitter (Roboski community leader; He speaks Turkish and Kurdish.)

- Hikmet “Reber” Alma on Twitter @reberalma (Gulyazi community leader; He speaks Turkish and Kurdish.)

- Shekh Alyas on FaceBook – shekhalyas (he will reply when he has internet access).

Alyas may be contacted by phone from within Turkey at 0538 249 48 75. If you put money on his Turkcell phone for calling within Turkey or pay for incoming overseas calls or SMS messages, he will be grateful. He is seeking sponsorship and work as a translator or environmental safety specialist.

Partial List of Belediyesis (city hall governments) aiding Ezidi Refugees:

- Diyarbakir Belediyesi

- Batman Belediyesi

- Siirt Belediyesi

- Şirnak Belediyesi

- Uludere Belediyesi

- Hilal Belediyesi

- Cizre Belediyesi

- Silopi Belediyesi

- Midyat Belediyesi

Dr. Amy L. Beam promotes tourism in eastern Turkey at Mount Ararat Trek (http://www.mountararattrek.com) and writes in support of Kurdish human rights. Follow her on Twitter @amybeam or email her at amybeam@yahoo.com.

Follow other news stories by Amy L Beam at http://kurdistantribune.com/?s=amy+l+beam

.jpg)