Translated by Yasin Aziz:

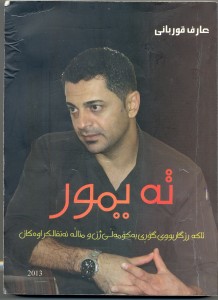

Taimoor Ahmad was 12 in 1988 when Saddam’s Anfal campaign began in Garmyan/Calar. This is a translated summary of his interview with the Kurdish journalist Aref Qurbani which appeared in Kurdish in the book, ‘Taimoor, Only Survivor of the Anfal Campaign’.

My name is Taimoor Ahmad. I was born on 1st January 1976. My mother’s name is Sarah Muhamed Mahmoud, from the village of Kullajo in Calar region. We were a family of six: my mum, dad, me and my three sisters. I remember them very well. We had a very happy life. How can I forget them? We were very close family, like most Kurds having very strong family and social relations.

I will never forget my family until the day of judgement, when we may meet up again. My family, all of them, were very handsome. My father was from the Rokhzayie tribe, with his big moustache, and with his black and white turban tight on his forehead. My mum was very beautiful, tanned and slim, with sweet features. My sisters took after my dad, light skinned and tall, with dark eyes and hair. I was the eldest child; my sisters Gielas, Snoor and Lawlaw were born after me.

Our village was about 40-45 houses, with no electricity and tap water. We had our spring water source, and some of us had a well. When the spring water source ran out, sometimes in late spring, we used the wells to get water. We had a small primary school, and I was with about 20 pupils in my class. All of my school friends – Azad, Saman, Sirwan and Ata – were caught in the Anfal campaign. They were all shot dead by the Iraqi soldiers. I think none of them survived the mass killing.

My father was a farmer. We moved to the town of Calar for a while, but when my father was called up to the Iraqi army – to put it in an official way – to go to war, he did not go. He refused to get involved in the senseless killing of war. “Why should I kill anyone?” he said. He refused to go, and we moved back to the village. I learned about this as he talked with relatives and neighbours. I was too young to understand what really was going on.

I remember all of my childhood, whatever happened. How could I forget the mass killing of our neighbours, family, relatives, my classmates? At the time I did not understand why anything like this should happen to us, or to anyone.

I remember when I was very young, when the Iraqi army often came to our village, killed our people, and the helicopter gunship was shooting us. They burnt my mum’s uncle’s (Khursheed’s) car. Another time they bombed and burnt a pick-up car that belonged to someone we knew, Mr Ata Hadji Hamajan. Oh I watched as it was burning, but why? I didn’t understand. I can’t remember the exact dates of those dreadful events No, I can’t remember all of them, but I clearly remember when I saw the helicopters, tanks, soldiers were aiming their guns at us. At the time, it seemed like it was the era of death, with bombing and there was fighting all the time. When the revolutionaries, the peshmarga – Kurdish freedom fighters – came, they took the tractors and cars of the village, they drove them to get around. As soon as the government knew that they were around, they started bombing us with the long-range artillery bombs.

Especially at night, if they happened to see any tractors or cars headlights they would start bombing our villages. And during the day, they would send their helicopter gunships, to bomb and shoot at us. Why they were doing this? These were our homes, villages, country – why they were coming? I couldn’t make out why, I was too young. Overall, our life was miserable. We could not lead a normal life, especially if one was an army deserter. One of these was my dad, he did not go to war and so we were always worried. As I was got older, I begun to understand more, and was getting anxious. I had a fear that, if they arrested dad, they would shoot him. All the family was worried that one day he might be caught and killed by the Arab army.

I remember when our people heard that the army and jash/mercenaries were coming. All the army deserters and the ones who were known to be with peshmarga groups were running away to hide. They created or dug up places, tunnels underground to go and hide. My father was one of them. I often went with him, we were very close to each other, and I always wanted to be with him. Some of his friends were annoyed when they saw me. They were worried that I might make a noise and give them away, and for us all to be murdered.

Even when my dad went to the other villages with his daily chores, he took me with him. We were very close, I even helped him with his farming and looked after the herd of sheep. We were a very happy family, all my family, we all loved each other. We enjoyed every minute of being together, it was a heaven of life, if they just let us live, but they didn’t. I often thought, even when there was a war, if you are with loved ones, your worries are lessened. Even though our village life was very difficult and dangerous, I thought our family togetherness healed most of the wounds of anxiety and fear.

Even before when I was born, our village was often under attack, from artillery bombs, tanks and the Iraqi air force, I didn’t know why even our shepherd with the herd was shot dead by the government forces. Our farmers were just doing their farming and had no guns but the helicopters shot them dead. I did not understand why the government was doing this. I remember when the men were going to town, and the kids wanted to go with them, their elders would often say, “No, you can’t come, the government soldiers will arrest you”. That was how they put them off. That was how we were brought up with fear.

As our life was always a war and we were fearful of an attack, my father had a Kalashnikov gun. Many of our villagers had one, not all of us, only those who could afford it. The peshmarga forces liked this.

I remember once there was a fight between the government forces and the peshmarga gunmen in the village of Sarqalla, near our village. I went with my dad and my uncle Usman to have a look from a hillside near our village.

We saw from far away something like fire balls and heard thunder-like noise. I asked my father, “What happens if an artillery bomb comes and hits us?”

“It is just the thunder bolt, don’t worry.” he replied.

He knew that I was scared, and after a few minutes he said, “Let’s go home.” That night I was scared, I could not sleep, my dad came and cuddled me in bed. I heard the explosions were coming nearer. My father fell asleep but I did not. After a while, there was a big explosion, which made everyone wake up. When my dad opened the door, we saw a fire on the hill where we had been watching the fight earlier. My father looked at me and said, “It was good that we listened to you and came home”. It did not take long before another bomb exploded nearby, and then we all went into the bomb-shelter under our front hall.

Inside the bomb-shelter it was damp, but my mum brought a sack of straw and scattered it around to make it comfortable for us. A bit later, we found out that the big explosion had hit the house of Rustam Hamajan, killing his wife and two children and wounding another child. I feel shivers in my body, when I remember this.

No one slept at all that night. In the morning all the villagers got together to help bury the dead. That day we all left the village, as we feared that the government would come back to bomb us. It had happened many times. We all knew that, when the villagers left their houses, and the government came and plundered all the houses and were busy with looting; so they left us for a while when they were busy taking our property.

We were not aware what was happening in the other villages, as there was no electricity and TV in our village, and we did not know when the army would come back to attack us. A few families had radios, but these never said was happening, as the government did not allow any media coverage to come into the area. They not only looted our property and houses, they even set them on fire. They burnt our harvest, and took our cattle and sheep herds.

We gradually became stranded; we were not allowed to leave, or to settle in the town or the cities. We were not able to go anywhere and we were worried. Even the Kurdish revolutionaries did not like it if we abandoned our villages. The ones who wanted to leave, they were not going to let anyone know. They were trying to leave secretly. However, there was a risk. If we were caught, we did not know what was going to happen to us.

We knew we could not hide in the fields anymore. There was no way to defend our villages, no forces left in the area. The government was ready with its air force, tanks and thousands of soldiers.

Every day was becoming worse for us, especially when we realised that all our villages were surrounded by the Iraqi army’s tanks and soldiers. We thought this is it, we are finished, no way to escape.

We hoped that we could reach one of the cities. We tried through one of the mercenary/jash heads hoping that he would be able to help us to get to the Smoud camp. That was where some villagers had been gathered by the regime, near the town of Calar. Those of us who decided to take this route boarded three tractors, with some necessary household belongings, and headed to Tilaco village to reach the Smoud camp.

Tilaco, a bigger village, it was about 15 minutes from our village. The rest of the villagers stayed at home. After we set of, we heard the army bombing our village. They shot fire flares in the sky above us. We turned our tractors headlights off and tried to hide, in case they would bomb us. We sent a few men to try and find Mustashar the mercenary head, but he was not to be found: either he was scared or he had lied to us.

That night in Tilaco was very scary; we were very tired and hardly slept. The next day we needed to head towards Mlasura village. It was only a 30-family village, and we had to take all our food with us, as they already had many guests from the other villages. It took us about half an hour to arrive, and the army did not come yet. Oh, it was such a frightening situation, it is impossible to describe, it was like the end of the world. We did not know that the way we were going was safe enough to survive. We did not know if we should surrender ourselves or let the army arrest us; we were desperate and we had not a clue what to do.

It was said by some that, if we went ourselves to the army, that would be better than if the army arrested us. We were not sure what to do. We stayed there for three days, and every day more people from the other villages were arriving. We really did not know why so many people were heading towards Mlasura. Whether they thought they would be saved, I do not know.

After the third day, the army came to Mlasura. We thought they were coming to take us to a camp to settle somewhere else. We would be included in the government amnesty. Many people believed that this was the case. We really wanted a way out, so that the helicopter gunships would not come to shoot us or bomb us anymore. And we had heard earlier that the government had built concentration camps near the towns and cities for us to settle there, so we would not be living in danger anymore.

It happened before to many other villagers, when they were relocated to many collective camps, so they would not be living under any threats of bombing, killing, plunder or danger. The people were very happy to leave their villages, as if they were heading towards peace and heaven, because we were so fed up with the life we had.

The transport links between the villages were very poor, and most of the villagers used tractors. There were hundreds of them when they were gathering in the Mlasura village. I remember we felt like we were in the convoy of a wedding party, when people were enjoying the trip so much. If we had known what the government was going to do to us, we would have tried to escape from Mlasura. Oh God, if we knew that the government was going to shoot us all or bury us alive. It crossed no one’s mind what they were doing to us, as we could not imagine that the government would forcibly arrest, kill all these families, children, old and young, that they would force us under the soil into mass graves, even before we were dead.

Some who had no tractors and came on foot, were put in army lorries. We were surrounded by many tanks, soldiers and helicopters. We were heading towards Quoratwo, which was another big village, where there was a concentration camp.

We all thought that we would be given new houses or places to live, but on the way we were guarded heavily. Many women came on the roadside and they all were crying, and the soldiers fired fire bullets above the crowd of families and children. When we arrived in the Smoud camp, there was no one to register anyone to be given a place to stay.

As we thought it was an amnesty, even if we had been guilty of anything, we never expected what they were going to do to us. All these families were still on their way, not knowing what they were heading into. Even if they considered that our men were guilty of something, or even criminals, but why also the families, the old and the children? We all were worried: what was going to happen to us? Oh God, what was happening; our worry and anxiety started again.

When we did not stop at the Smoud camp, we were getting worried, what they were going to do with us? “The army deserters will be taken out”, we thought. They would be sent to do army service, as they needed recruits. Alternatively if they were going to shoot them, why should the government also arrest all of the women and children? I was worried about my dad. I was worried we were going to be separated. I was thinking that, if they arrested him, I would go with him and they might show some sympathy because of me. I never wanted to be separated from him. I was also worried that, if they never released us, then my mother and sisters would be left alone; who should look after them? Oh God, what a frightening situation it was. I was thinking, and pleading with God to save us, to release us so that we could go back to Calar town or to the Smoud camp. “Why does God not come to our rescue, what have we done to be punished like this?” I thought.

When we were in the Mlasura village, we expected that the army and the jash/mercenaries would come to kill us all, but later when they came and didn’t kill us, this gave us some hope. The head of mercenaries told us, “You will go to a camp, they will give you a place to stay”. So we felt happy, as we were reassured that they would not kill us. I was thinking that, if we settled somewhere, I would go back to school. I was in the second year, but my age group were all in year five. I did not care as long as we were safe and treated well. I thought the school would consider my age, to put me in a higher class. I knew I would cope, I loved going to school and learning. That was the only way to get out of this misery. I thought I was going with my sisters; I would be holding their hands to go to school.

There, I thought, we would be away from the helicopters, government tanks and soldiers who often came to bomb and shoot us, to kill us, to burn our houses and destroy our farms. We would be some place where we would not be scared anymore. Nevertheless, when we were on the road, going somewhere we did not know, there were many families on the roadside and they all were crying for us. When we passed the Smoud camp, and the town of Calar, many women came on the road and they all were crying for us. Oh God, what was happening, they must know, something bad was going to happened to us. We never knew what was going to happen.

They took us to Quoratwo castle. It was a big castle, I had never seen anything like that, and the village building was all made of mud bricks. It was a big place, with a big entrance, all the tractors headed in, and everyone gathered there. We all stayed there, as they kept bringing more villagers.

They did not give us any food, and only brought water by tankers. Most of the people had their own food and some household belongings, but the ones who did not have food were helped by others. Many of the villagers had brought their sheep herds. They had them until they reached the edge of the town, and then the Iraqi army plundered all of them. They brought us a few tankers of water, but it was not enough, as they kept bringing more people.

.jpg)

Does it hold true that some Kurdish official held talks with Saddam in the wake of “Halabja Genocides”. Who facilitated brutal dictator to perpetrate genocides against the Kurds? Was not the world intelligence services aware prior or in the middle of such war crimes? Why did they remain silent and who and why are they providing sophisticated weapons of mass destruction to Iraqi military now?

All Kurdish HRs, Genocides Watch, NGO are urged to closely observe such developments in Baghdad to prevent the repetition of Anfals, Halabjas and Barzanis Genocides.